By James Barnett

As of May 2023, the National Student Clearinghouse published their annual Current Term Enrollment Estimates, painting a bleak picture of the state of college enrollment across the nation. Public two-year enrollments dropped 10.1% over the preceding year in 2021, 8.2% in 2022, and rose 0.5% in 2023, respectively.[i] Public four-year enrollments have also shown the same general downward trend but at slower rates—0.3% in 2021, 1.2% in 2022, and 0.8% in 2023. The Estimates also found that “undergraduate-level students are shifting the types of credentials they pursue, with enrollments in bachelor’s degree programs falling more steeply than associate’s (-1.4%, -114,000 students versus -0.4%, -15,000 students) and other undergraduate credentials showing enrollment growth (+4.8%, +104,000 students).”[ii]

According to Brookings, in recent years the public has become increasingly apathetic towards the perceived value of a college education. Data sourced from a Wall Street Journal poll revealed that 56% of respondents did not believe that college is worth today’s costs, a statistic that showed only 40% from the same survey in 2013.[iii] This perception could be caused by a number of factors—including cost, political climate, and decreasing population of youths.

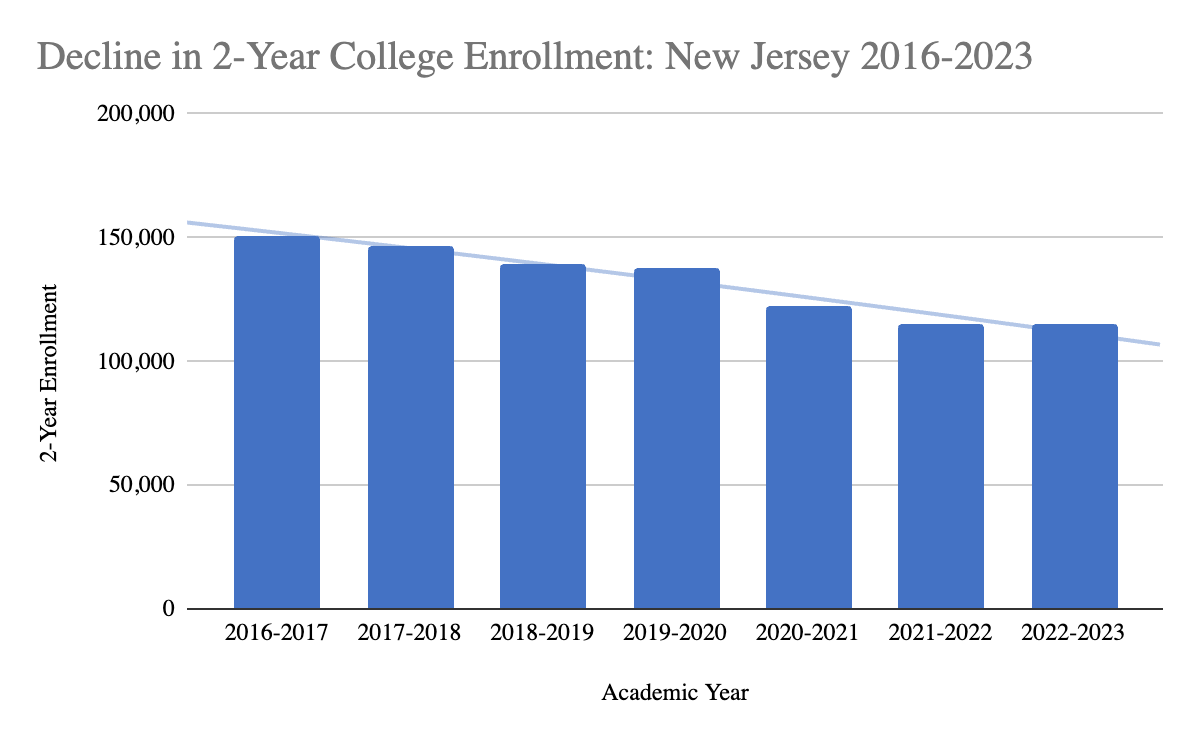

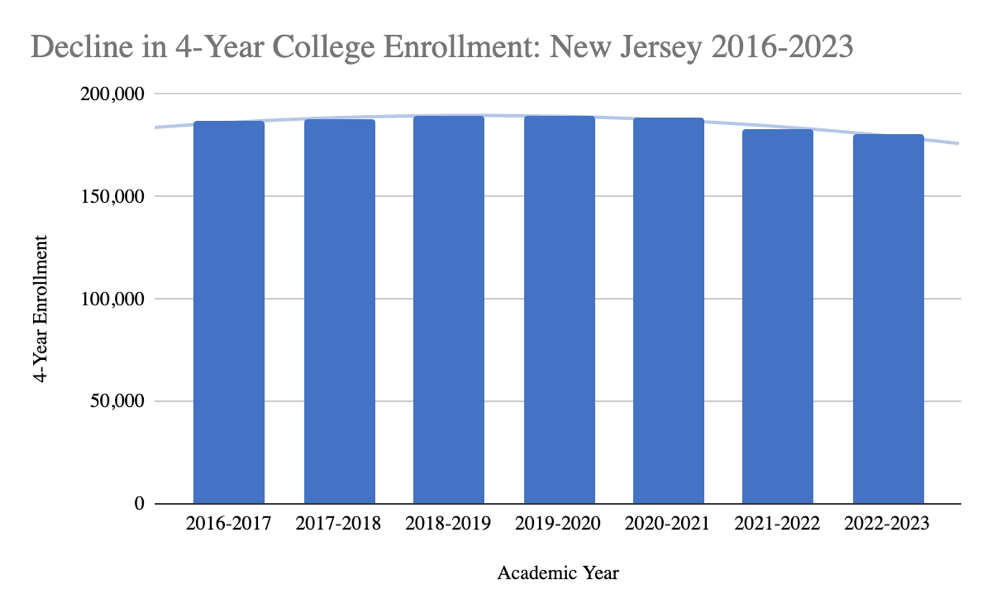

These national trends are almost identically mimicked by data compiled by the New Jersey Office of the Secretary of Higher Education, which publishes state post-secondary enrollment data going back to the 2016-2017 academic year. Figures 1 and 2 below show that both two- and four-year enrollments have declined over the past seven academic years, representing a 31.0% decrease in enrollment in two-year county colleges and a 3.6% decrease for four-year public universities statewide.

Figure 1. Decline in 2-Year College Enrollment: New Jersey 2016-2023 [iv]

Figure 2. Decline in 4-Year College Enrollment: New Jersey 2016-2023 [v]

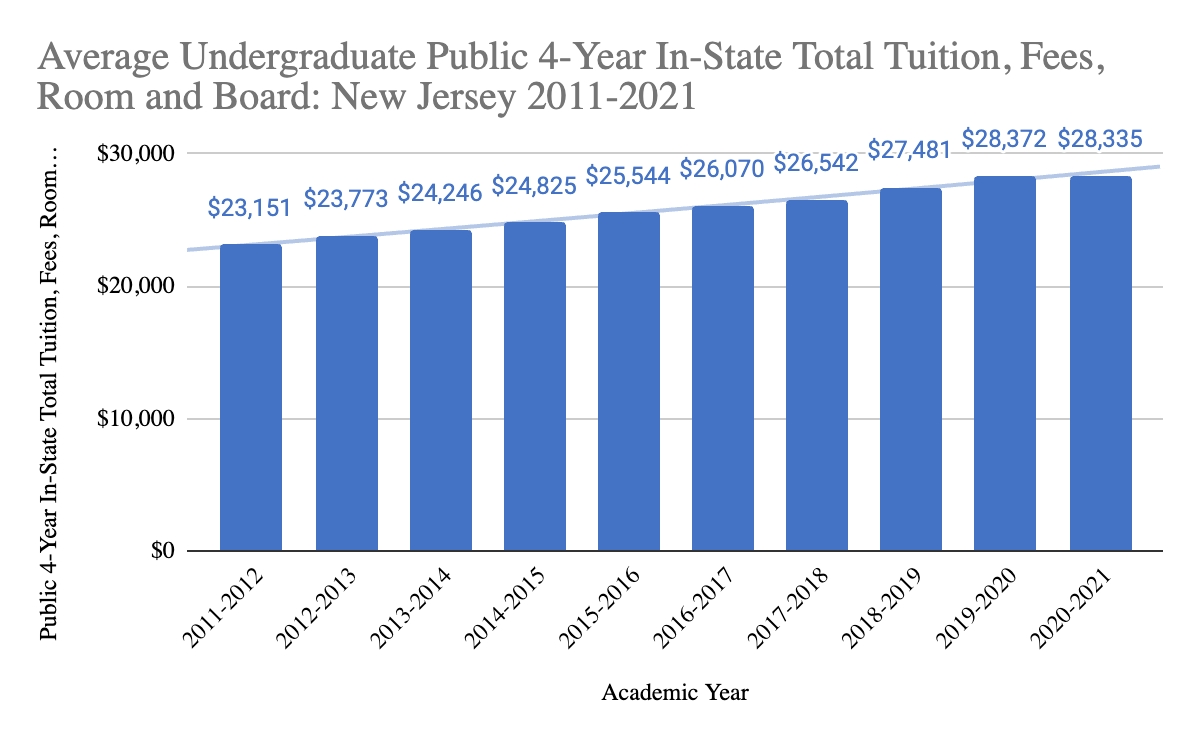

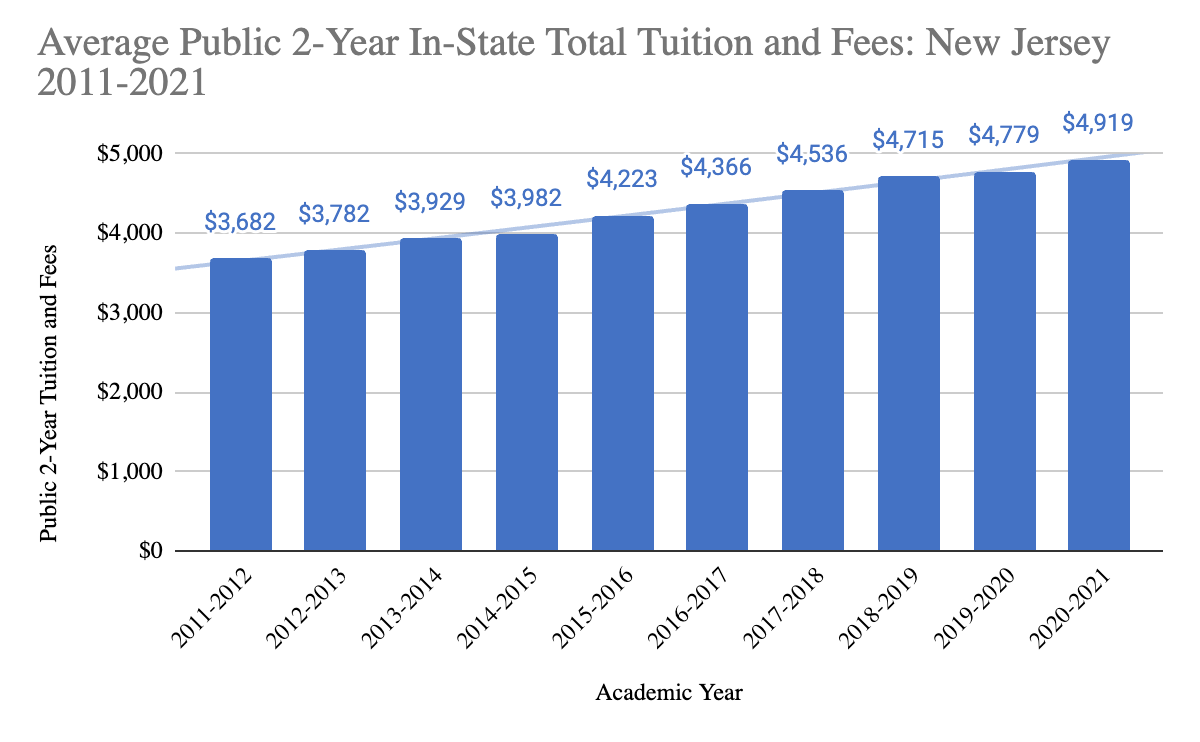

While this perception and subsequent enrollment decline could be attributed to multiple broad factors aforementioned, rising enrollment cost is one major source that is quantifiable in New Jersey. For the 2020-2021 school year, average public in-state undergraduate tuition, fees, room, and board totaled $28,335 for students. Yet, New Jersey only spends $2,038 on average per-student in terms of financial aid.[vi] Additionally, only 16.2% of undergraduates at two-year institutions receive student loans; the most common type of financial aid given out by states. Figures 3 and 4 below show the year-after-year change in average costs per-year to attend public institutions in-state for New Jersey undergraduates:

Figure 3. Average Undergraduate Public 4-Year In-State Total Tuition, Fees, Room, and Board: New Jersey 2011-2021[vii]

Figure 4. Average Public 2-Year In-State Total Tuition and Fees: New Jersey 2011-2021 [viii]

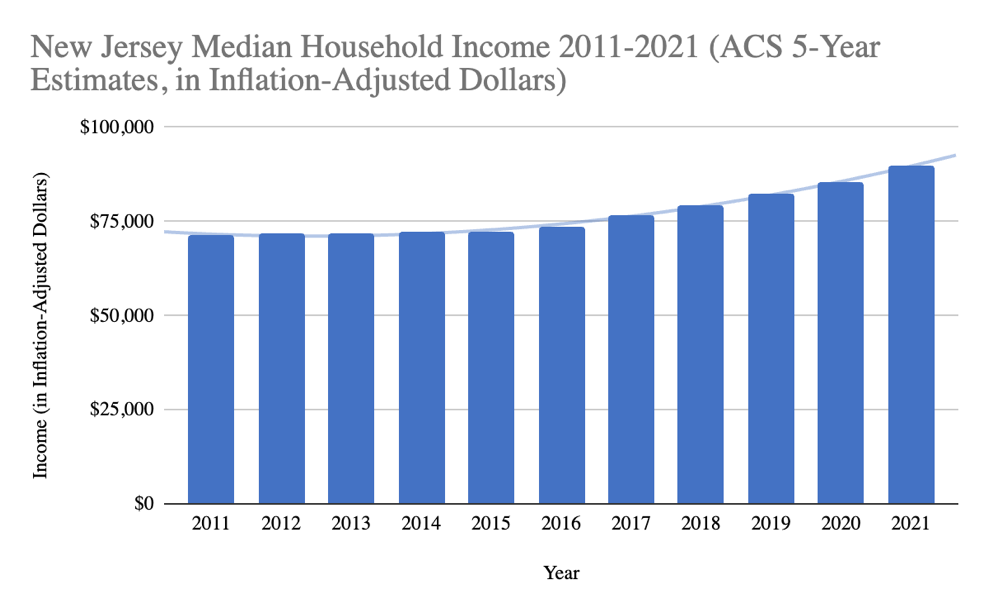

Tuition is not the only cost to New Jersey students and their families that support them that continues to climb year-after-year. Commonly regarded as one of the most expensive states in America to live in, the median household income in New Jersey (in 2021 inflation-adjusted dollars) had stayed stagnant for many years, but most recently has begun to trend upward sharply. According to American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Estimates sourced from the U.S. Census Bureau, median household income in 2021 had reached $89,703 in the Garden State whereas just ten years prior it was over $18,000 lower, even when adjusted for inflation. This change is reflected in Figure 5:

Figure 5. New Jersey Median Household Income 2011-2021 (ACS 5-Year Estimates, in Inflation-Adjusted Dollars) [ix]

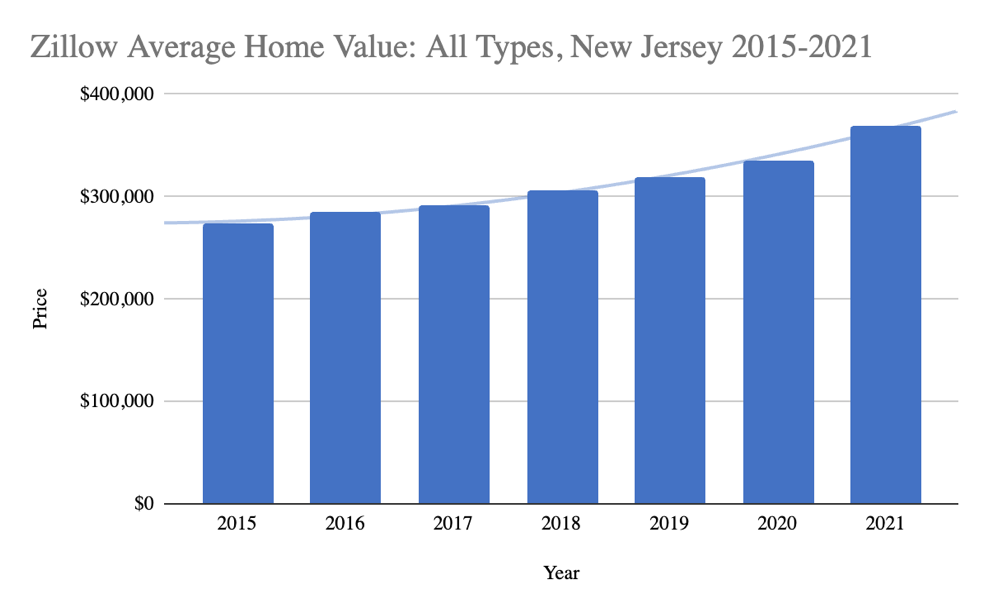

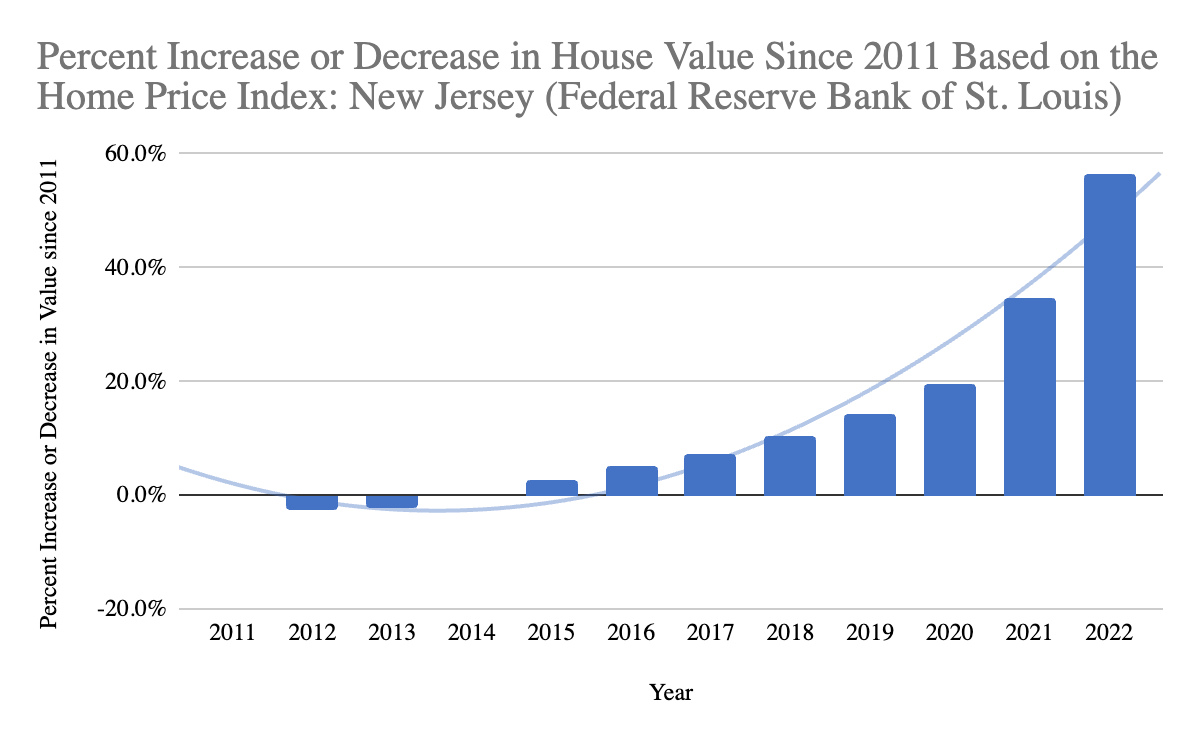

To further quantify the severity of the change in wealth and cost-of-living over the past ten years in New Jersey, we use the cost of buying a home as a standard measure. In 2021, the average value of all types of homes sold in the state was $369,824, reflecting a 26% overall increase in dollar amount from the same figure in 2015 (shown in Figure 6).[x] Showing this trend even more drastically is the Home Price Index (HPI) developed by the Federal Reserve Bank, which shows that 2022 average house values in New Jersey reflect an increase of 56.5% since the average 2011 value; rising 21.8% in just one year (the 2021 numbers showed an increase of only 34.7%).[xi] Figure 7 shows the changes in value as measured by the HPI year-after-year, most recently reflecting these volatile increases as described.

Figure 6. Zillow Average Home Value: All Types, New Jersey 2015-2021[xii]

Figure 7. Percent Increase or Decrease in Home Value Since 2011 Based on the Home Price Index: New Jersey (Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis) [xiii]

Clearly, this paints a picture that as cost-of-living rises in New Jersey synchronously with cost of tuition, attending college is likely seen as more and more unattainable for students without ample financial resources. This is especially true for non-traditional degree seekers, who may have more crucial and time-sensitive financial obligations such as feeding a family or making a rent or mortgage payment (after all, the median full time daycare bill for an infant in New Jersey was $1,040 a month alone in 2019).[xiv]

Another factor that could be affecting enrollment is attitudes of high school students. According to Anthony Iacono, president of the County College of Morris, “there has been a shift in priorities for recent high school seniors. During an American Association of Community Colleges conference this past spring, survey results showed most high school students are saying: “I know I need to do something after high school, but not necessarily college.””[xv] Because of this, colleges have started to focus recruitment efforts on non-traditional, older students to meet enrollment demands.

These understood takeaways have also pushed many states to adopt financial aid programs aimed at workforce development for non-traditional students. These policies target aid directly to students in programs tied to fields where there are workforce shortages and overall economic growth; especially for skilled jobs that require less than a baccalaureate degree.[xvi] To close this “talent gap,” states have been investing in programs “to attract students from all ages, educational backgrounds and income levels… but policymakers are also finding that strategies must include financial support, since over half of jobs in the U.S. are held by adults who have no education beyond high school. And as SREB[Southern Regional Education Board]’s Unprepared and Unaware: Upskilling the Workforce for a Decade of uncertainty reports, two-thirds of estimated job growth by 2026 will be in jobs for people with at least some postsecondary education.”[xvii] This is also a priority at the national level, as federal legislation such as the ACCESS to Careers Act from 2021 has been introduced, investing money into work-based learning programs through community colleges. Advocates for these policies often emphasize that “students at community colleges often come from a variety of nontraditional backgrounds, whether they’re low income, first generation, adult learners or international students, and they require additional support services to ensure their success.”[xviii]

New Jersey has the ability to craft such a policy or set of policies using other states as examples that would increase financial aid for students and community college enrollment. These can also have the secondary effect of bolstering the workforce for “middle-skill” jobs that are often in high-demand.[xix] In Kentucky, the Work Ready Kentucky Scholarship Program (authorized by state statute) provides scholarships to citizens who have not yet earned a postsecondary degree in an industry-recognized certificate or an associate of applied science in one of the state’s high-demand workforce sectors as identified by the Kentucky Workforce Innovation Board. The Georgia HOPE Grant Program provides grants to residents pursuing a degree at any Georgia public technical college; also offering the Strategic Industries Workforce Development Grant which provides additional funding “for students already receiving the HOPE grant who are enrolled in certificate and diploma programs that prepare them for in-demand occupations.”[xx] Other high cost-of-living states like New Jersey that offer similar programs include California (the “Cal C” grant program), Maryland (the Workforce Shortage Student Assistance Grant Program), and Massachusetts (the Educational Rewards Grant Program Fund).[xxi]

To be successful in implementing such a program, New Jersey needs to commit to financing of student aid long-term and collaborate across many state agencies (such as the Department of Education, Department of State, and the Economic Development Authority) to identify areas of economic need and link them to accessibility to higher education. As the already high cost-of-living in the state continues to rise without any sign of cessation in the near future, it is imminently important to take into account that many of the potential students who could help New Jersey reverse its decline in higher education enrollment are very likely ones who are faced with financial barriers to entry, and ones who are older and less inclined to attend a traditional four-year university full-time. By linking education to job training and providing sufficient assistance to students pursuing associate and technical degrees (in addition to aid provided to four-year degree-seeking students), this population can be targeted more effectively.

James Barnett is a graduate student in the Edward J. Bloustein School of Public Planning and Policy at Rutgers University. He is working toward a Master of City and Regional Planning degree in 2024.

References:

[i] “Current Term Enrollment Estimates.” National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, May 24, 2023. https://nscresearchcenter.org/current-term-enrollment-estimates/.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Elizabeth Gellman, Katharine Meyer, Katharine Meyer, Bruce Jones George Ingram, Thinley Choden, and Katherine Silberstein Marguerite Roza. “The Case for College: Promising Solutions to Reverse College Enrollment Declines.” Brookings, June 29, 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-case-for-college-promising-solutions-to-reverse-college-enrollment-declines/.

[iv] “New Jersey OSHE Fall Enrollment Dashboard.” The Official Site of the State of New Jersey. Accessed August 18, 2023. https://www.state.nj.us/highereducation/dashboard-educationfall.shtml.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Hanson, Melanie. “Financial Aid Statistics.” Education Data Initiative. Education Data Initiative, February 15, 2021. https://educationdata.org/financial-aid-statistics#new-jersey.

[vii] “Digest of Education Statistics.” National Center for Education Statistics. United States Department of Education, Accessed April 21, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_330.20.asp.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] “Tables.” Social Explorer. Social Explorer, Accessed April 26, 2023. https://www.socialexplorer.com/explore-tables.

[x] “New Jersey Home Values.” Zillow. Zillow, Accessed April 26, 2023. https://www.zillow.com/home-values/40/nj/.

[xi] “All-Transactions House Price Index for New Jersey (NJSTHPI).” Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Accessed April 26, 2023. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NJSTHPI.

[xii] “New Jersey Home Values.” Zillow. Zillow, Accessed April 26, 2023. https://www.zillow.com/home-values/40/nj/.

[xiii] “All-Transactions House Price Index for New Jersey (NJSTHPI).” Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Accessed April 26, 2023. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NJSTHPI.

[xiv] Clark, Adam. “The Cost of Daycare in All 21 N.J. Counties, Ranked from Least to Most Expensive.” NJ.Com. Advance Local Media, January 22, 2019. https://www.nj.com/news/g66l-2019/01/f350923ebe9277/the-cost-of-daycare-in-all-21-nj-counties-ranked-from-least-to-most-expensive.html.

[xv] Zimmer, David M., William Westhoven, Mary Ann Koruth, and Philip DeVencentis. “‘Where the Heck Is Everybody?’: NJ College Enrollment Is Declining. We Asked Experts Why.” NorthJersey.com, September 1, 2022. https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/education/2022/09/01/nj-college-enrollment-decline-experts-weigh-in/65467129007/.

[xvi] Blanco, Cheryl. “Workforce-Driven Financial Aid: Policies and Strategies.” Essential Elements of State Policy For College Completion, (2019). Accessed May 9, 2023. https://www.sreb.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/essential_elements_workforce_financial_aid_2019.pdf?1570814566.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Gravely, Alexis. “Bridging the Workforce Training Gap at Community Colleges.” Inside Higher Ed. Inside Higher Ed, June 6, 2021. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/06/07/bipartisan-bill-would-authorize-millions-federal-grant-funding-work-based-learning.

[xix] DeRenzis, Brooke, and Rachel Hirsch. “Job-Driven Financial Aid Policy Toolkit.” Skills in the States (National Skills Coalition), (2016). Accessed May 9, 2023. https://nationalskillscoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Job-Driven-Financial-Aid-Full-Toolkit-Final.pdf.

[xx] Blanco, Cheryl. “Workforce-Driven Financial Aid: Policies and Strategies.” Essential Elements of State Policy For College Completion, (2019). Accessed May 9, 2023. https://www.sreb.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/essential_elements_workforce_financial_aid_2019.pdf?1570814566.

[xxi] “State Policy Models for Connecting Education to Work Financial Aid for Workforce Development.” Education Resources Information Center. United States Department of Education, July 1, 2019. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596780.pdf.