By Anna M. Dulencin and Itzhak Yanovitzky

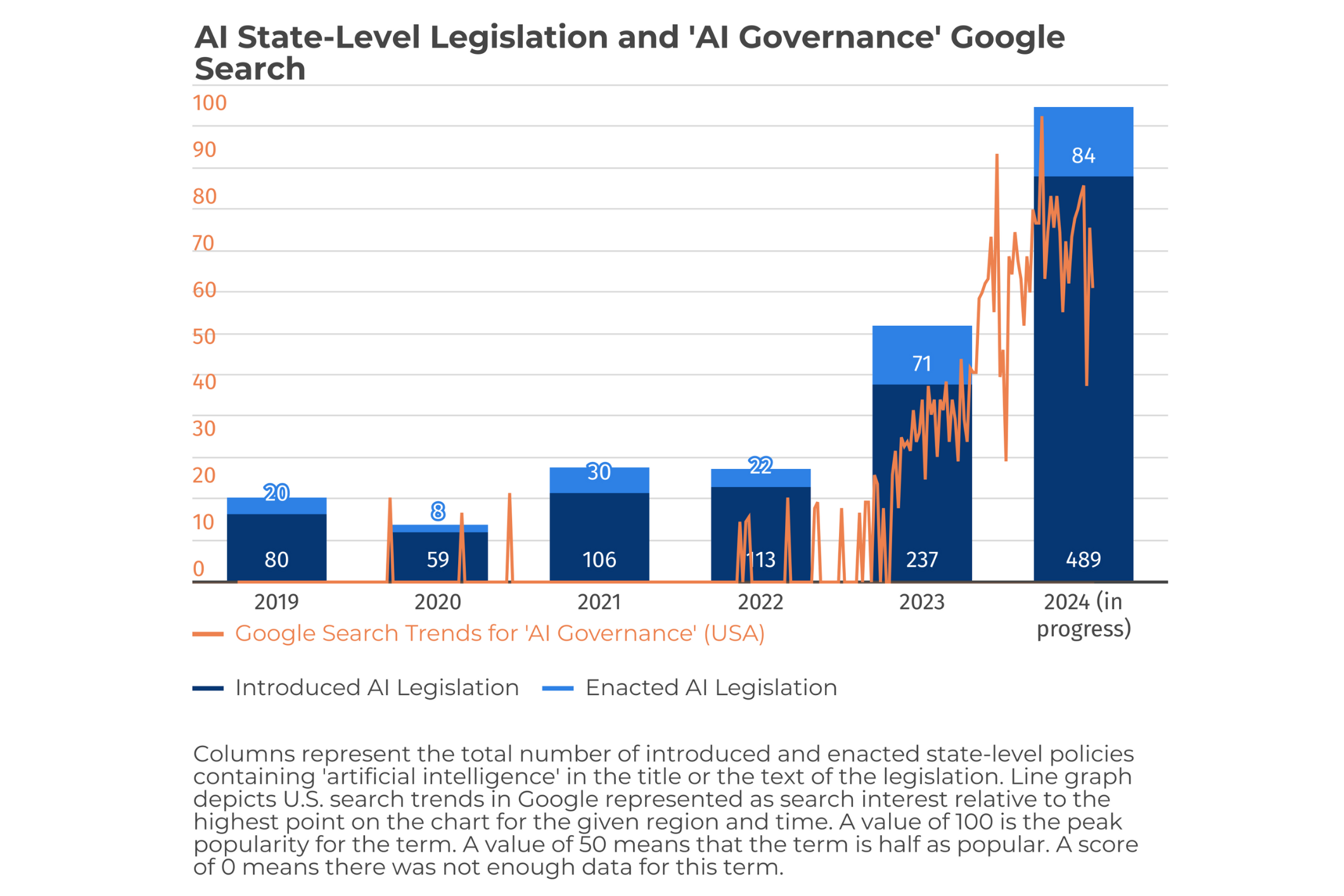

Scientists and non-scientists alike have been surprised by the pace at which artificial intelligence (AI) is penetrating all aspects of life and society. Interest in the potential applications of AI and their associated benefits and threats has too peaked rapidly, particularly after the introduction of ChatGPT in November 2022, and is increasingly dominating public and policy discourse (Fig. 1, above) and preoccupying scientists across a multitude of disciplines and fields. Governments worldwide are struggling to keep up with the speed of AI innovations and urgent calls for regulatory actions. Some governments are plowing ahead with regulations designed to curtail potential harmful effects of AI, most notably the European Commission (EC, the executive body of the European Union) that recently adopted the AI Act, but response from the federal and state governments in the U.S. is still lagging, largely because this is a complex policy issue which many policymakers, especially in state legislatures, feel unequipped to tackle.

Scientists must work together with policymakers and the public to shape sound AI policy that harnesses its potential to benefit individuals and society while placing checks on its potential to cause harms. There is already a great deal of insights from across scientific disciplines and professional practice fields that can productively inform policy discourse but does not effectively reach federal and state policymakers. There are many well documented barriers to efficient and productive flow and exchange of knowledge between science and policy, particularly when scientific complexity and politics get in the way, but research on the use of research evidence in policy generally highlights the important role of evidence intermediaries in bridging the gap. Much of this work is focused on intermediaries outside of governments—e.g., think tanks, expert panels, professional associations, and journalists—but the most influential intermediaries may be the ones already embedded in government because they have established relationships and routine access to policymakers.

Building on previous findings that STEM-educated state legislators often champion evidence-informed policies and serve as trusted sources of scientific information for their colleagues1, this project aims to explore the feasibility and efficacy of leveraging their position and influence to share relevant insights from research and advocate for sound (evidence-informed) AI regulation.

To achieve this, we are undertaking a three-pronged approach. First, we are expanding and updating an existing database of all STEM and healthcare experts elected to U.S. state legislatures. This comprehensive resource will provide a foundation for understanding the landscape of STEM representation and in-house expertise at the state level.

Second, we will track the progress of all existing state-level AI-related legislation, including the evidence it is based on, and share our findings in real time through a publicly accessible resource, which will also be used for generating a quarterly policy brief tailored for state policymakers. This analysis will not only provide valuable insights into current legislative trends but also identify potential gaps and opportunities for evidence-based policymaking.

Finally, we will target dissemination of resources and policy briefs to STEM-trained state legislators and track their legislative activities, including bill sponsorship, co-sponsorship, committee work, and other communication such as press releases and social media posts. This will help us understand how these legislators engage with AI-related issues and whether their STEM backgrounds influence their legislative behavior.

Anna M. Dulencin, Ph.D. is the director of the Eagleton Institute’s Science and Politics Program, and Itzhak Yanovitzky, Ph.D. is a professor at the Rutgers University School of Communication and Information.

References:

[1] Bogenschneider, K., & Bogenschneider, B. N. (2020). Empirical evidence from state legislators: How, when, and who uses research. Psychology, public policy, and law, 26(4), 413.