Redlining, Disinvestment, and Health Outcomes

Within both the state of New Jersey as well as the broader U.S., there has existed a historical practice of redlining, which is defined as the practice of systematically denying various services (e.g., credit access) to residents often based on race and primarily within urban communities, (Egede, 2023). Not only was this practice instrumental in separating the areas of housing and business investments, it often reflected in home values and neighborhood safety rates (Fitzpatrick, 2020), and also placed limitations on the quality of health resources, such as hospitals and primary care services.

To better understand the far-reaching impacts of redlining, a study was done using the Mapping Inequality data to identify which Medicare recipients lived in redlined neighborhoods and their incidence of heart failure (Mentias, 2023). Overall, the results showed higher rates of chronic illnesses for Black residents regardless of redlining in comparison to White residents. It was also noted that Black beneficiaries in redlined areas had a higher incidence of heart failure in comparison to Black beneficiaries in non-redlined areas. The authors noted that social determinants of health and structural racism had an impact on the health conditions of ethnic minorities.

A New Jersey Cities Case Study

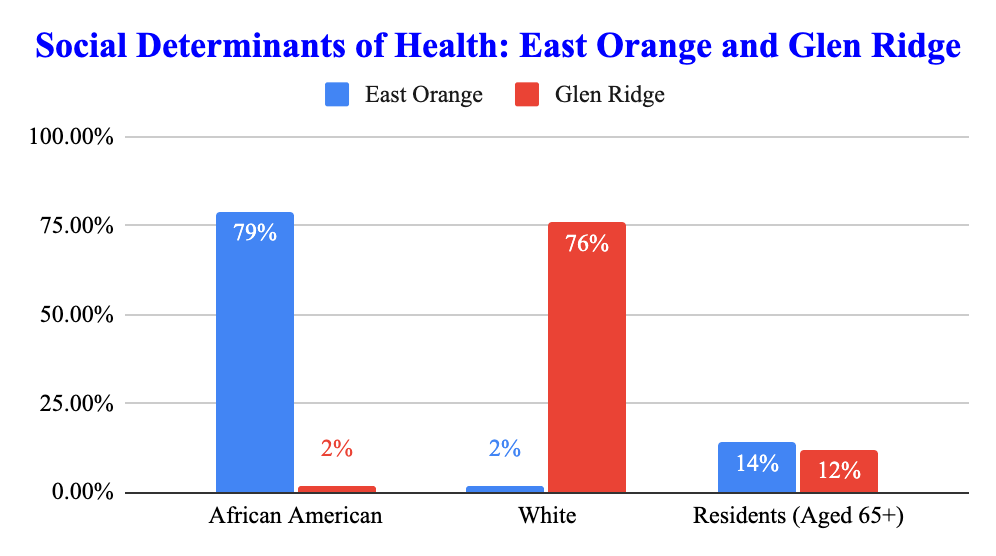

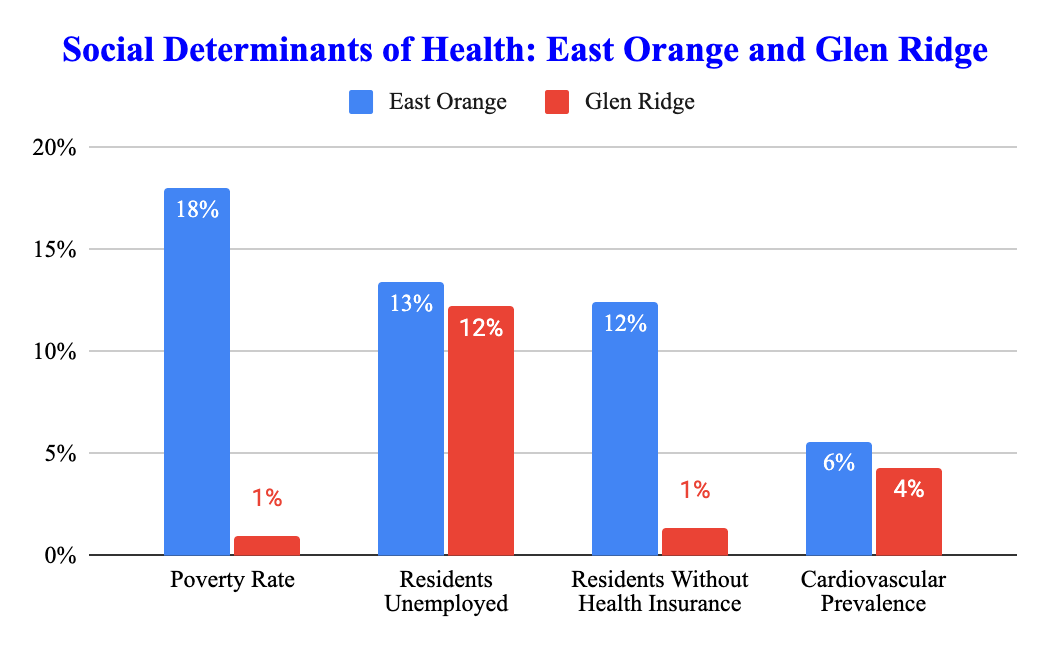

Within the state of New Jersey specifically, this blog examines the suburban municipality of Glen Ridge in comparison to the more urban municipality of East Orange, focusing on how location can impact health outcomes. These cities are located in the same county and share a city border. However, even with such a close proximity to one another, there are stark differences in the social determinants of health for each community, including median income, population ethnic proportions, educational achievement levels, health insurance access, and cardiovascular presence. For Glen Ridge residents, the median level of education was 41% for both master’s and bachelor’s degrees with less than 1% having less than a high school diploma. For East Orange residents, the median level of education was 6% for master’s and 15% for bachelor’s degrees with 14% having less than a high school diploma, (Census, 2022). In East Orange, the median income is around $43,527 while in Glen Ridge the median income is around $256,000 (Census, 2022). These factors relate to the health outcomes for residents dealing with heart disease in both communities, and all have a large impact on public health efforts and personal advocacy for health.

Source: 2022 Census data.

Regardless of socioeconomic status or educational attainment, state legislation aims to support the health of both communities (Peterson, 2020). However, as shown in the graphs above, the gaps in health outcomes are still very prevalent. The disparities featured are a large cause of the continued health equity gap (Odeny, 2021).

New Jersey Solutions

New Jersey overall seems to be moving in the right direction toward addressing the healthy equity gap, however the performance and implementation locally can be improved in many different ways, including place-based support in many areas including public health education (Fitzpatrick, 2020). And while overarching “big policy” changes can be important to focus on, the role that lower institutional level groups play on positively impacting a community is just as important (Peterson, 2020).

To better improve upon health outcomes in New Jersey, it is suggested that an integrated healthcare model that supports health care literacy and accessible resources should be implemented across all cities to lower the risks associated with chronic health and one’s environment. Progress within health policy towards a more health equity-focused society can only be achieved by looking at the past and defining the importance of community.

Tanaya Watson is a dual B.S./M.P.H. undergraduate student pursuing a major in Public Health and a minor in Biological Sciences at Rutgers University. Tanaya was also one of eight students selected to participate in the New Jersey State Policy Lab’s third annual Summer Internship program.

References

Egede, L. E. Walker, R. J., Campbell, J. A., Linde, S., Hawks, L. C., & Burgess, K. M. (2023).

East Orange city, New Jersey—Census Bureau Profile. (n.d.). Retrieved July 25, 2024, from https://data.census.gov/profile/East_Orange_city,_New_Jersey?g=160XX00US3419390

Fitzpatrick, K. M., & Willis, D. (2020). Chronic Disease, the Built Environment, and Unequal Health Risks in the 500 Largest U.S. Cities. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(8), 2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph1708296

Glen Ridge borough, New Jersey—Census Bureau Profile. (n.d.). Retrieved July 31, 2024, from https://data.census.gov/profile/Glen_Ridge_borough,_New_Jersey?g=160XX00US3426610

Gollust, S. E., Fowler, E. F., Vogel, R. I., Rothman, A. J., Yzer, M., & Nagler, R. H. (2022). Americans’ perceptions of health disparities over the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from three nationally-representative surveys. Preventive Medicine, 162, 107135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107135

Health promotion practice, 22(6), 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839920950730

Modern Day Consequences of Historic Redlining: Finding a Path Forward. Journal of general internal medicine, 38(6), 1534–1537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08051-4

Odeny B. (2021). Closing the health equity gap: A role for implementation science?. PLoS medicine, 18(9), e1003762. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003762

Peterson, A., Charles, V., Yeung, D., & Coyle, K. (2020). The Health Equity Framework: A Science- and Justice-Based Model for Public Health Researchers and Practitioners.