Introduction

New Jersey is home to one the largest populations of students with disabilities (SWDs) in the United States. Almost one-fifth of our public school students aged 3 to 21 are served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The need to accommodate this significant portion of the student population posed unique challenges in ensuring they received the education and support they were entitled to during the pandemic.

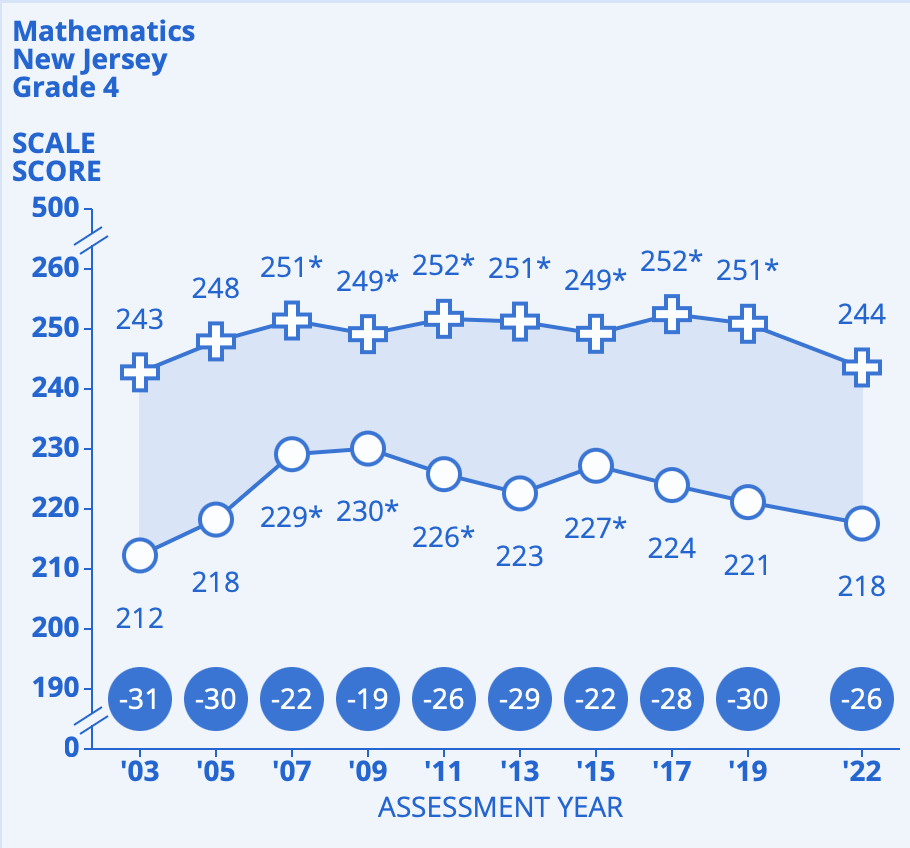

The achievement gap, which refers to the disparity in academic performance between students with and without disabilities, persists post-COVID-19 pandemic. Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress show that there has been a gap in various subject areas for the past decade. This pressing issue requires immediate attention and action by state and federal governments.

Figures 1 and 2 show a drop in overall academic performance in the first school year post-COVID-19, 2021-2022, for 4th-grade students in standardized assessments for mathematics and reading. This highlights a massive area for concern as the average scores for both student populations decreased. This was a pronounced decline among students with disabilities, who faced compounded challenges and accessibility barriers due to the transition to distance learning in March 2020.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Note: Students without disabilities are represented as a plus sign, while students with disabilities are represented as a circle.

What Happened During the Pandemic?

The pandemic exacerbated challenges for students with disabilities, and this contributed to the loss and ineffective substitutes for Individual Education Plans (IEPs). IEPs are specialized learning plans and related services designed to meet the unique needs of a student with a disability. In New Jersey, over 30 school districts asked parents to sign waivers that relieve them of any liability claims under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) during the pandemic. Some parents inadvertently waived their right to due process despite this move by school districts being a clear violation of state and federal law.

Some districts did offer special education and related services; however, this did not eliminate the challenges faced by SWDs. The digital divide, which refers to the gap between those with access to digital technologies and those without, was a significant issue. Disparities in access to technology and broadband internet access meant that some SWDs did not have access to the internet and necessary technologies typically found in the classroom. These gaps in access can lead to a loss of learning and retention, further widening the educational divide. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in June 2022, public schools reported that, on average, 50% of public school students were behind grade level in at least one academic subject area at the beginning of the 2021-2022 school year, compared to the 36 percent at the end of the school year.

Post-Pandemic Legislative Process

In response to the challenges one of the state’s most vulnerable student populations faced, New Jersey passed two bills to address some gaps left by the pandemic.

The bill, S3434, passed in June of 2021, requires boards of education to provide special education and necessary services to students exceeding the age of eligibility for special education. This involves when a student reaches the maximum age of 21 during the school years of 2020-2021, 2021-2022, 2022-2023. However, due to the late signing of the bill, many students with disabilities who could have benefitted from these provisions had graduated. For other students, the decision for additional schooling is made between the student’s parents and their IEP team based on the student’s demonstrated need.

The bill, S905, passed in March of 2022, extended the period in which families with students with disabilities can file for a due process petition regarding the identification, evaluation, or educational placement that would ensure the provision of accessible and appropriate public education (FAPE) during COVID-19 school closure. A review of the 33 cases petitioning for compensatory services found that 80% were denied. The law does not stipulate any requirement of the New Jersey Department of Education to collect data regarding school district compliance.

Post-Pandemic and Beyond

While legislature efforts like S3434 and S905 were passed to address the challenges faced among the state’s students with disabilities population, questions remain about their actual effectiveness in supporting SWDs post-pandemic. The pandemic brought awareness to the challenges faced by SWDs but, unfortunately, also exacerbated them.

Students with disabilities (SWDs) must receive a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) from their school districts, which is especially critical post-pandemic, where the widened existing barriers to educational access are evident. School districts can do this by providing compensatory services for students exhibiting pandemic-related learning loss, identified through individualized-needs-based assessment at the start and throughout the instructional period. As mentioned earlier, the challenges prompted by the digital divide can be combated by individual school districts. Doing so by appropriating technology and internet access to SWDs who are eligible under Title 1—lastly, making resources available to families of students with disabilities (SWDs) so that they are aware and can take advantage of their legally entitled resources and benefits. School districts must address these compounded challenges, which can be done with or without external regulation so that students with disabilities (SWDs) can regain lost progress and thrive in their educational environments post-pandemic.

Jordyn Roy is an undergraduate student double majoring in Political Science and Public Policy at the School of Arts and Sciences and the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University. Jordyn was also one of eight students selected to participate in the New Jersey State Policy Lab’s third annual Summer Internship program.

References:

- Broege, N. C. R., & Anderson, C. (2020). Inequality in Isolation: Educating Students with Disabilities during COVID-19. In G. W. Muschert, K. M. Budd, M. Christian, D. C. Lane, & J. A. Smith (Eds.), Social Problems in the Age of COVID-19 Vol 1: Volume 1: US Perspectives (1st ed., pp. 91–100). Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv15d81tx.14

- COE – Students With Disabilities. (n.d.). National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a Part of the U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg/students-with-disabilities

- Fast Facts: Back-to-school statistics (372). (n.d.). National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a Part of the U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372

- Gómez, J. (2023, January 13). NJ doesn’t collect data on COVID-related law for students with disabilities – Chalkbeat. Chalkbeat; Chalkbeat. https://www.chalkbeat.org/newark/2023/1/13/23553612/new-jersey-department-of-education-students-disabilities-covid-law-makeup-services-parents/

- NAEP Dashboards – Achievement Gap. (n.d.). The Nation’s Report Card. Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/dashboards/achievement_gaps.aspx

- NJ Legislature. (n.d.-a). New Jersey Legislature. Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2020/S3434

- NJ Legislature. (n.d.-b). New Jersey Legislature. Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2022/A1281

- Ruhela, V. S. (2023). The impact of remote and blended learning on special education: Recent trends and implications.

- Waters, L. (2024, February 9). 80% of NJ Students With Disabilities Denied Services – NJ Education Report. NJ Education Report. https://njedreport.com/80-of-nj-students-with-disabilities-denied-services/

- What Special Education Parents Need to Know Now that S3434 Has Been Signed. (2021). Education Law Center. https://edlawcenter.org/assets/files/pdfs/publications/S3434%20Fact%20Sheet%20Updated%20July%207%202021%20CORRECTED%20FINAL.pdf