By Tarun Reddy Arasu

An increasing disparity is developing between individuals who possess the means and abilities to access and utilize the internet and digital technologies and those who lack such resources and expertise.[1] This digital divide is making it more difficult for those who are less affluent to obtain an education, thereby posing a threat to their economic wellbeing. It is important for governments to bridge this digital divide to improve educational and economic opportunities for all.

Digital access is crucial to obtain information and social services, pursue education and employment opportunities, use healthcare platforms, and communicate with others. Alarmingly, the most vulnerable populations, (i.e., low-income families, racial and ethnic minorities, the elderly, and women), are more likely than others to lack such access.

According to a recent report by the Pew Research Center, 21% of parents of K-12 schoolchildren say that their children are very or somewhat likely not to finish their schoolwork because they do not have access to a computer at home. In the same survey, 22% of parents with homebound children report having their children finish their homework using public Wi-Fi, while 29% say it is at least somewhat likely that their children will have to complete school assignments on a cellphone.[2]

The Digital Divide in New Jersey

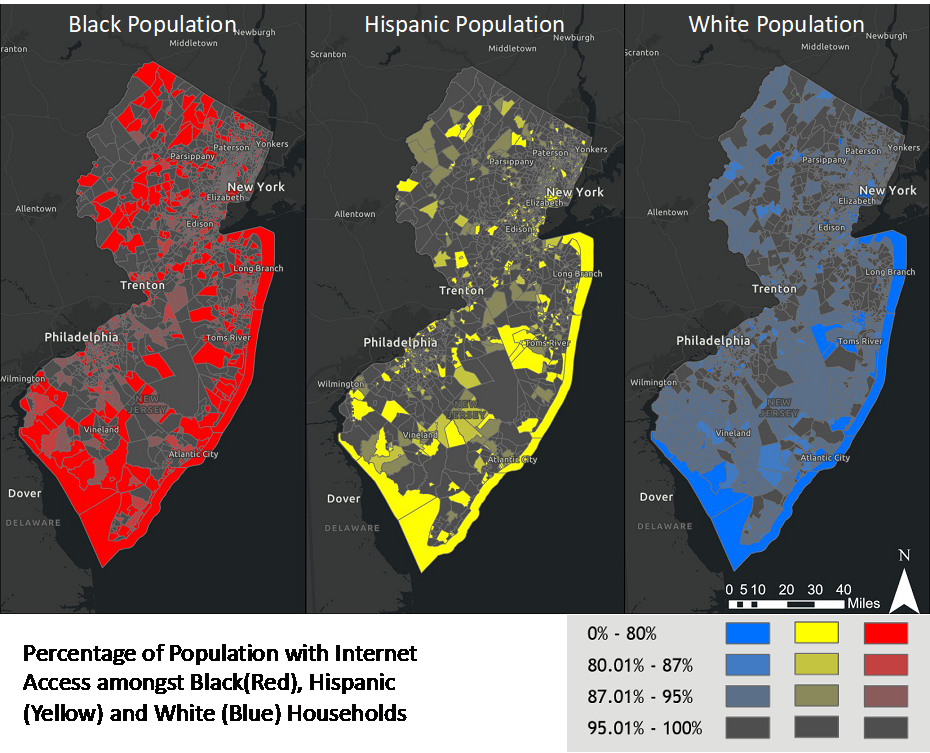

The digital divide is closely tied to economic opportunity, and the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected Black workers, leading to high levels of unemployment.[3] Additionally, Black-owned small businesses have struggled during the pandemic and rely on internet access to adapt to a market that is increasingly reliant on online services. To understand the digital divide in New Jersey, we mapped American Community Survey data from 2020 and observed if there is a correlation between race, education, and employment with access to the internet and digital technology. The following were the observations:

Digital and Internet Access Segmented by Race/Ethnicity:

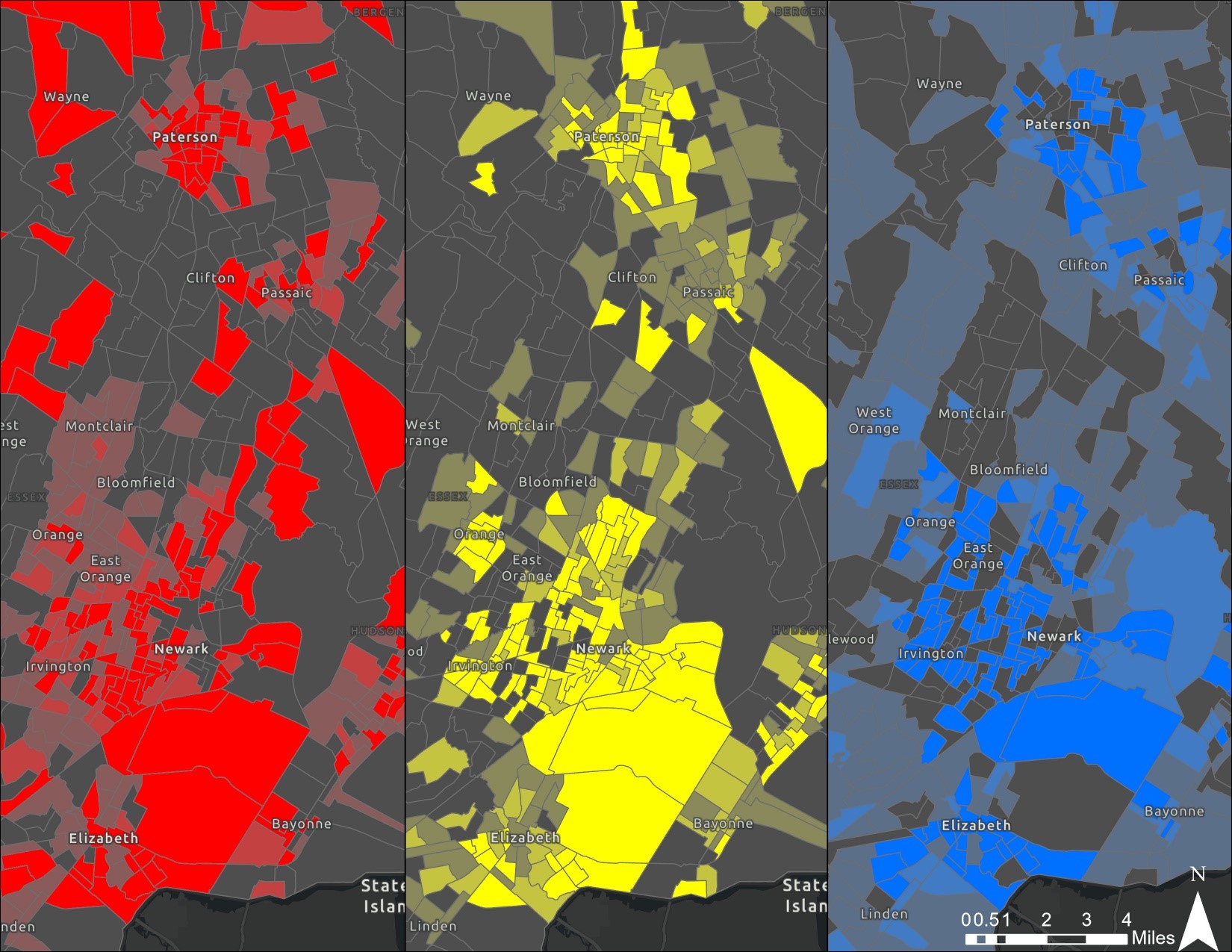

Newark Close-up:

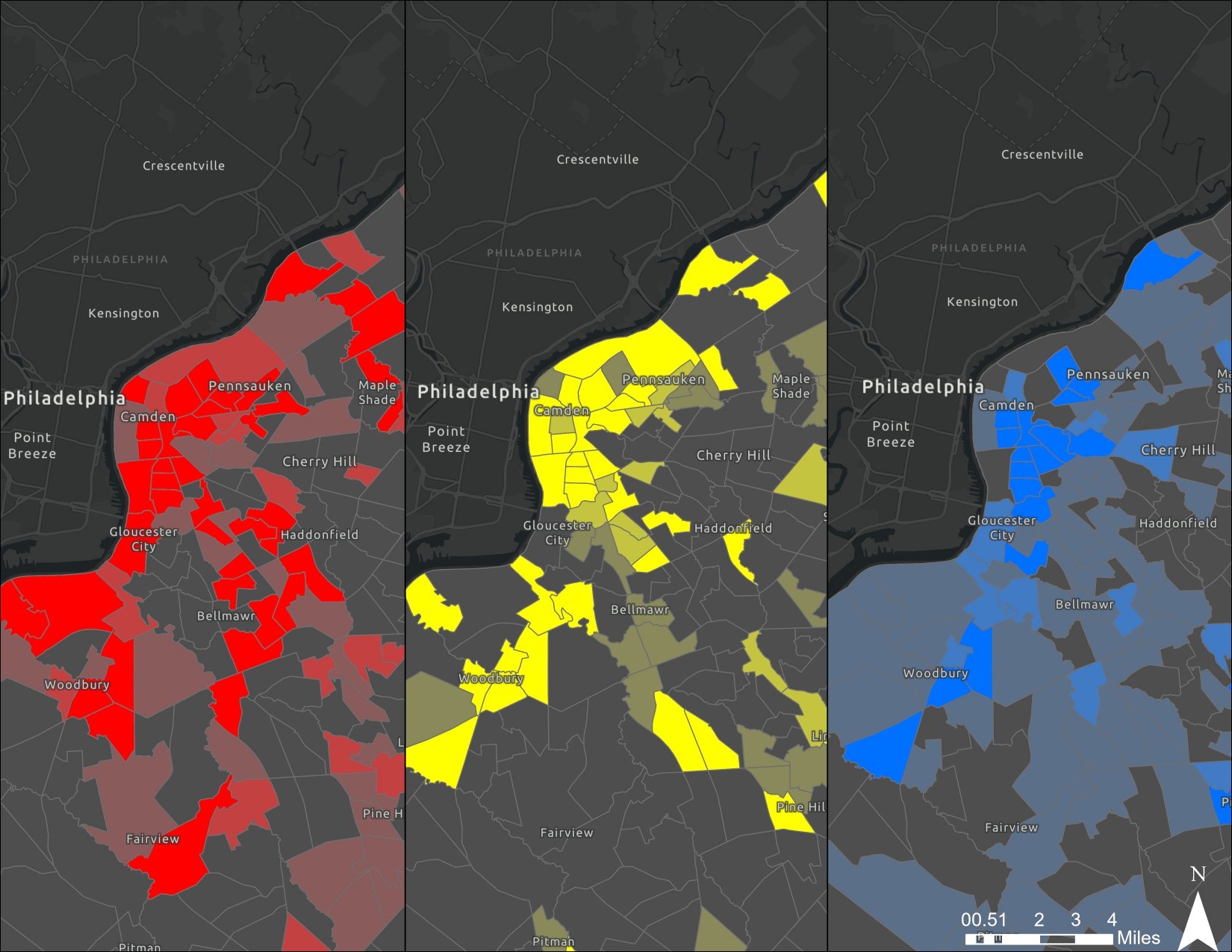

Camden Close-up:

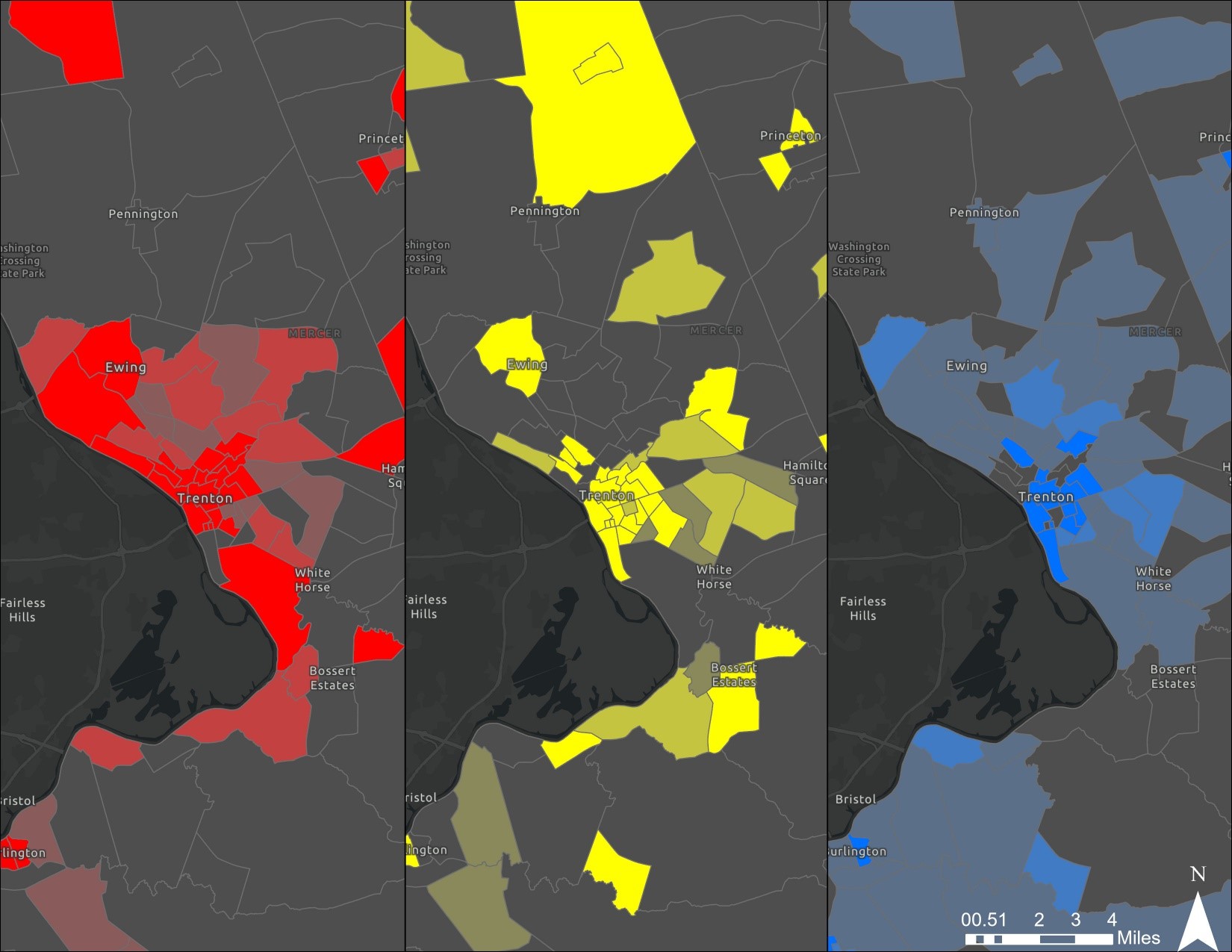

Trenton Close-up:

The above maps clearly show unequal access to the internet and digital technology for these racial and ethnic subgroups. Approximately 14% of Black and 13% Hispanic population in households in New Jersey do not have access to the internet and a computer, compared to 9% of White households in New Jersey. The difference is more pronounced in the communities of Newark, Trenton, and Camden where the median income is $41,335, $39,718 and $30,247 respectively (all less than 50% of the state median income).[4] One quarter of all households in Newark (23%), Camden (23%), and Trenton (26%) lack access to the internet. Given the importance of our cities, digital equity is of critical importance to the economic vitality of the state.

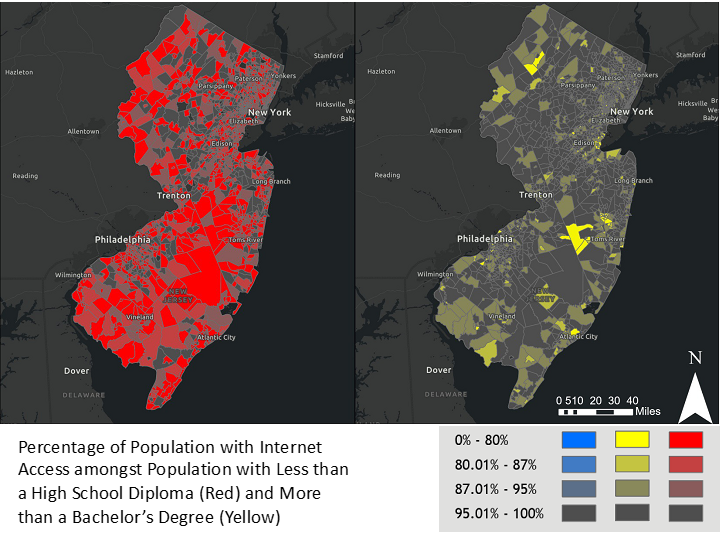

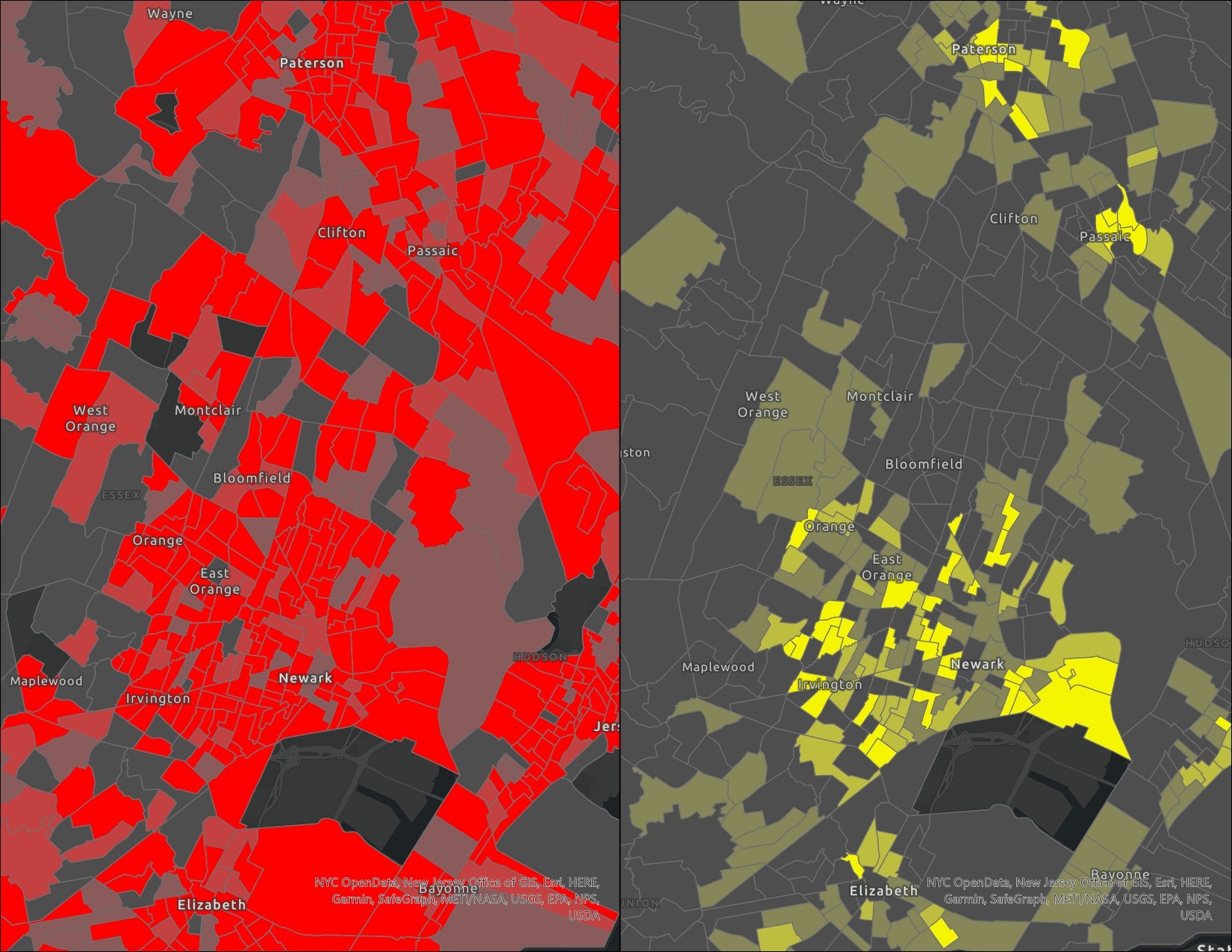

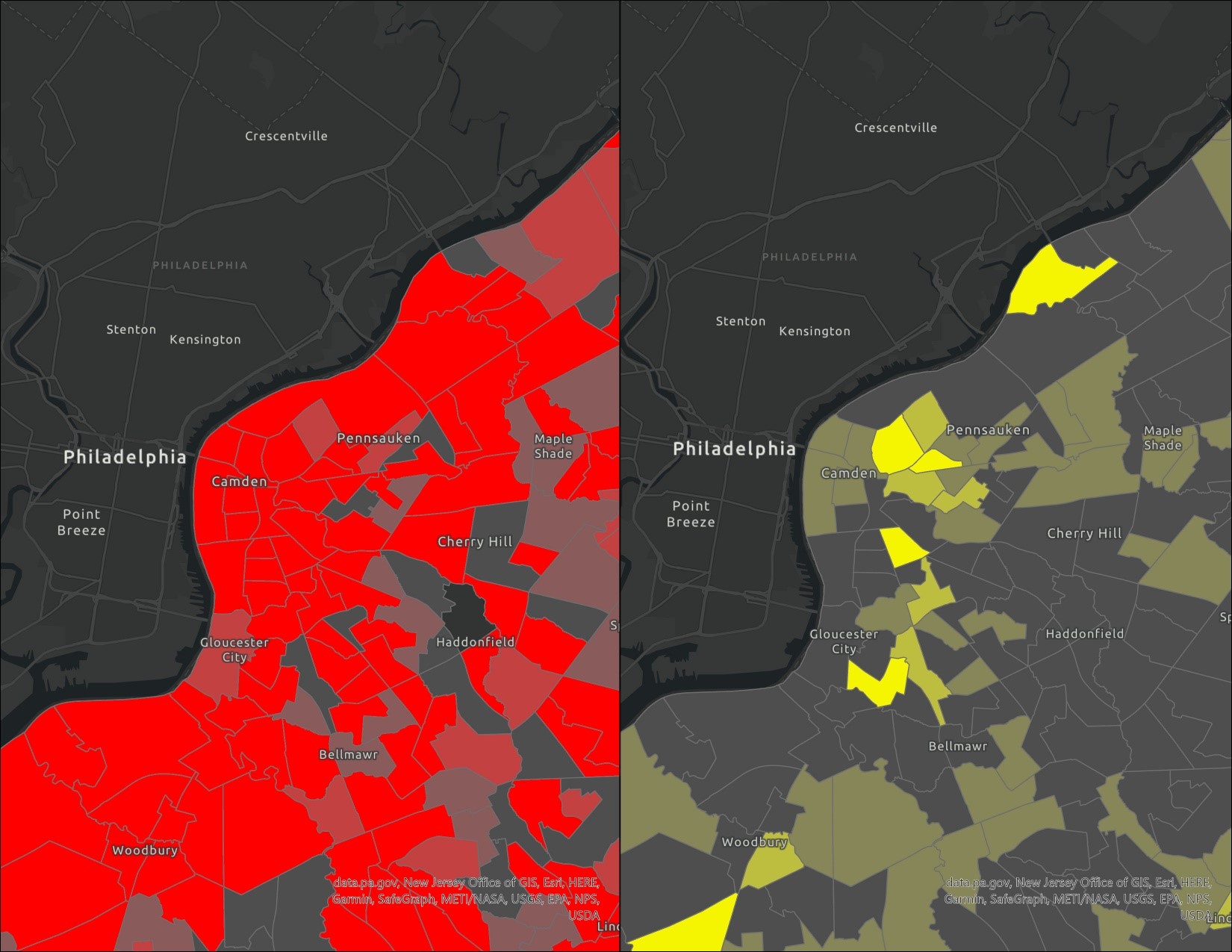

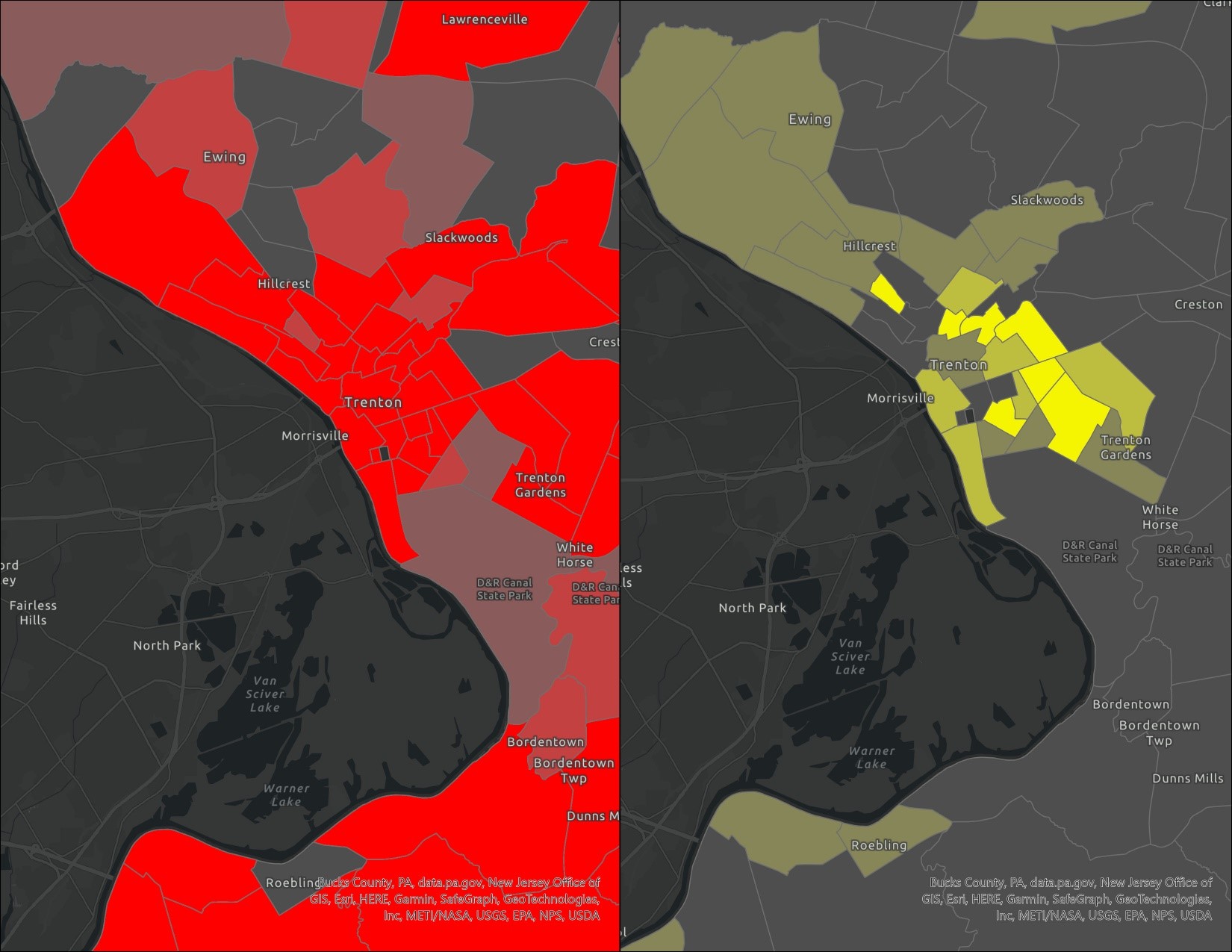

Digital and Internet Access Segmented by Education:

Newark Close-up:

Camden Close-up:

Trenton Close-up:

Education is one of the most important factors associated with access to internet and digital technologies. Based upon American Community Survey (ACS) data, amongst population 25 years and older more than a quarter (27%) of those with less than a high school degree does not have access to internet, compared to smaller shares of those with a high school diploma (12%) or bachelor’s degree or higher (4%).

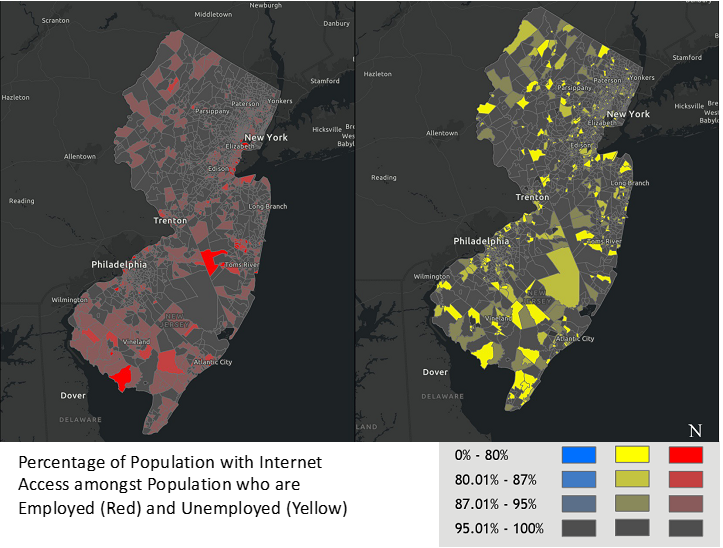

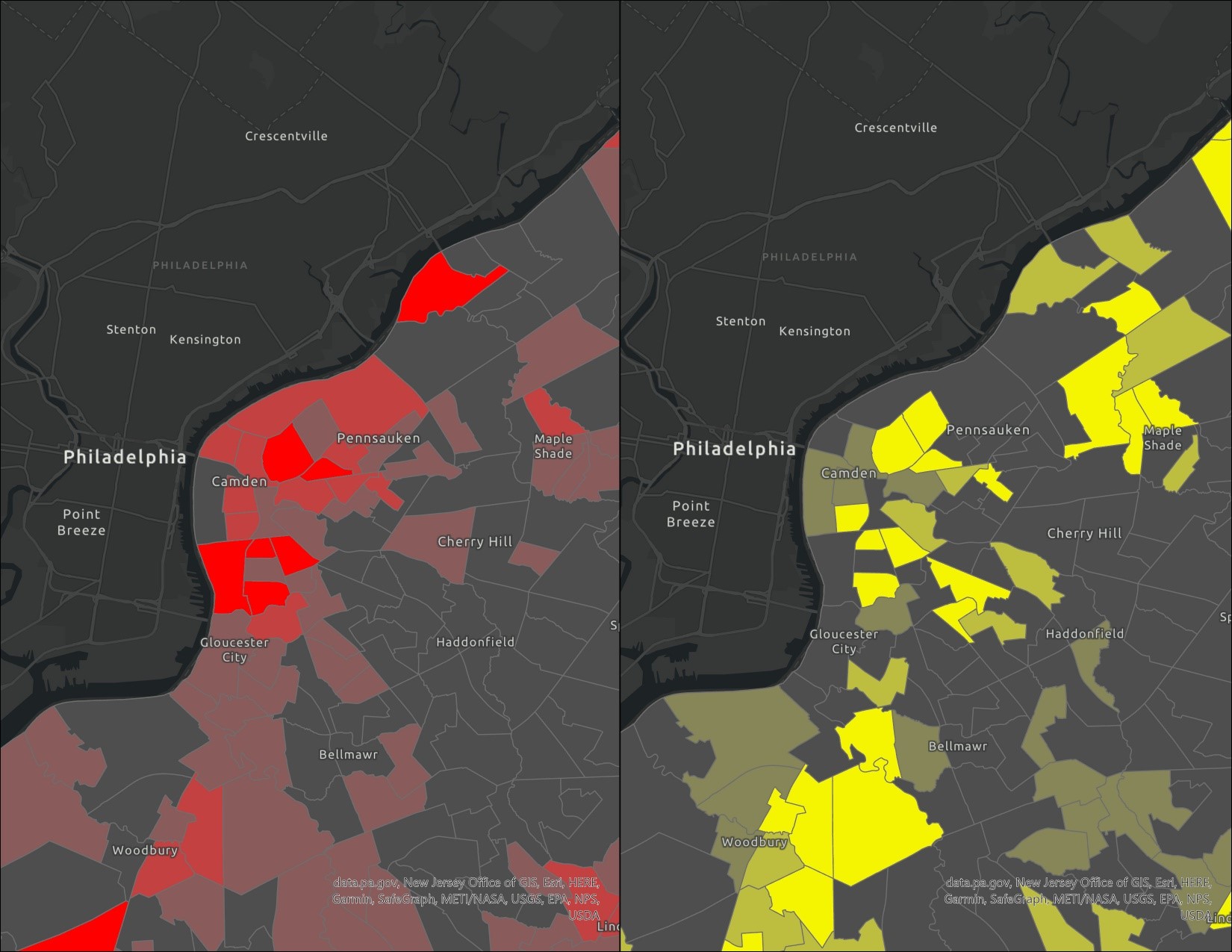

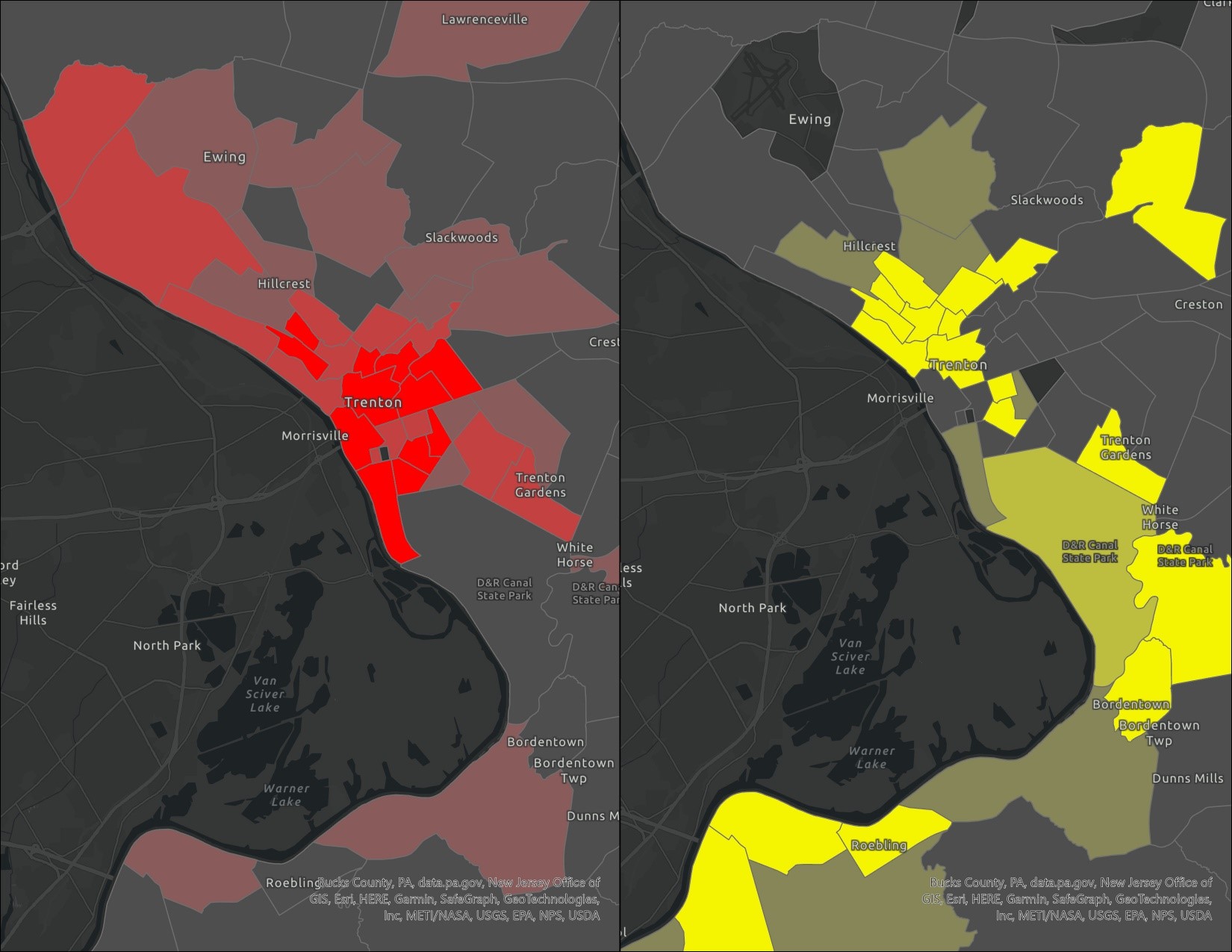

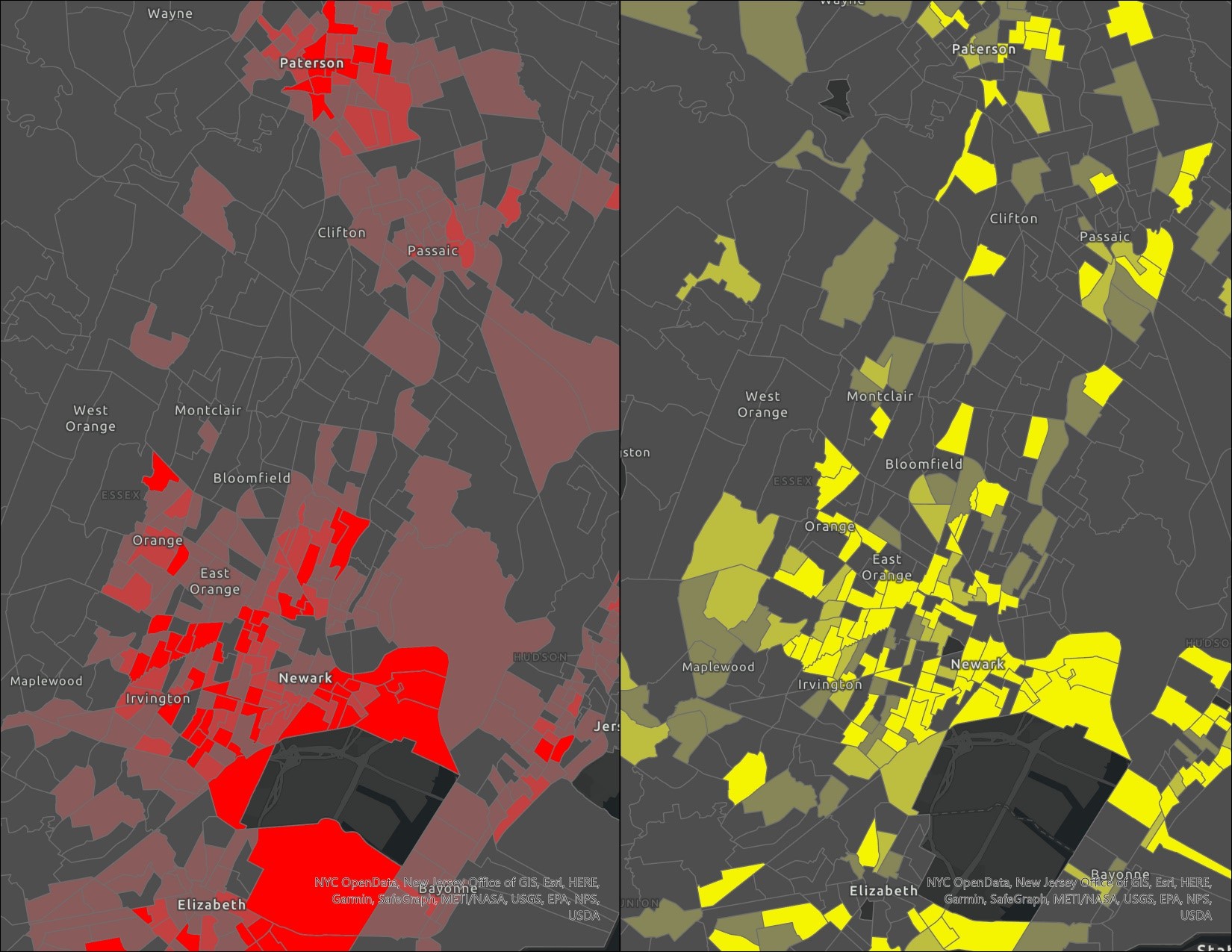

Digital and Internet Access Segmented by Employment Status:

Newark Close-up:

Camden Close-up:

Trenton Close-up:

Employment status is also associated with internet access. According to the ACS data, 5% of the employed population does not have access to the internet, compared to 10% of the unemployed population. Importantly, 20% of civilians 16 years or older New Jersey who are not part of the workforce lack access to the internet.

Conclusion

The transition from print to digital media has revolutionized communication, made education more accessible, and opened new economic opportunities. Unlike the printing press, which took centuries to have a widespread impact, the shift to digital has occurred over just a few decades. Leaders in cities across New Jersey should work together to address this digital divide in a fashion tailored to the specific needs of each community. This bottom-up approach would give local governments the freedom to experiment, learn, and adapt from successfully implemented solutions across the state.

References:

[1] Some digital divides between rural, urban, and suburban America persist | Pew Research Center. (2021). https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/19/some-digital-divides-persist-between-rural-urban-and-suburban-america/

[2] Emily A. Vogels, Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption, Pew Research Centre. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/22/digital-divide-persists-even-as-americans-with-lower-incomes-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/

[3] Terrell-Simmons, V. S. (n.d.). Bridging the African American digital divide: An analysis of computer and Internet access and usage trends among African American graduates of digital divide programs in New Jersey [Ph.D., Capella University]. Retrieved December 19, 2022, from https://www.proquest.com/docview/305453528/abstract/B752B2BF05D54240PQ/1

[4] U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States

Digital Equity. (2007). In G. Anderson & K. Herr, Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412956215.n257

Geyer, V. E. (n.d.). Digging Through the Garden State’s Digital Divide: A Descriptive Retrospective Study of Differences in Educational Technology Resources in New Jersey Public Elementary Schools According to Socioeconomic Status, Percentage of Minority Students, Abbott Dist.

Gurstein, M. (2003). Effective use: A community informatics strategy beyond the Digital Divide. First Monday, 8(12). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v8i12.1107

van Dijk, J. (2005). The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452229812

Warschauer, M., Knobel, M., & Stone, L. (2004). Technology and Equity in Schooling: Deconstructing the Digital Divide. Educational Policy, 18(4), 562–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904804266469