By Maia de la Calle

Pandemic-related school closures posed several challenges to students and their families, including learning losses, adverse socioemotional and mental health outcomes, and food insecurity. The pandemic and associated school closures also negatively impacted educators; they rapidly had to adjust their instructional models to fit remote learning. These changes in instruction practices, coupled with health concerns and added pressures to address students’ pandemic-induced academic struggles and socioemotional needs, exacerbated teacher burnout. Data on the effect of burnout on teacher retention remains limited. Still, in March 2022, the National Center for Education Statistics reported that the pandemic increased staff turnover rates and that U.S. public schools continue “struggling with a variety of staffing issues, including widespread vacancies and a lack of prospective teachers.” To address staff shortages and fill “critical need” positions in New Jersey schools, Governor Murphy signed a bill in January 2022 that loosens pension guidelines (Bill No. 3685). This legislation assured that retired educators who return to work in AY2021-2022 or AY2022-2023 can receive a higher-than-average salary while still collecting their pension. This law not only applies to retired teachers but also other critical school staff, such as special education specialists. As of September 2022, approximately 100 New Jersey districts petitioned to hire retired educators under this new law. The legislation’s effect at the district level has been mixed, however. Some districts, such as Millville, struggle to attract applicants; while others, such as Newark, have recruited numerous retirees.

To better understand which New Jersey school districts have been most affected by staffing issues and, hence, likely to benefit from this legislation, we explore changes in student-teacher ratio, retention rates, and average years of experience from AY2017-18 to AY2020-21 (the last year for which data are available). Table 1 presents three measures of school staffing: the state’s student-teacher ratio (STR), one-year teacher retention rate, and teachers’ average years of experience for academic years 2017-2018 through 2020-2021. An examination of state averages for all three measures does not reveal the pandemic’s impact on school operations; in fact, they imply improvements have been achieved in retention and experience. However, it is important to consider that, as of AY2021-2021, the state had 669 school districts, including vocational and charter school districts and that averages might not accurately represent staffing change. Thus, the last column on Table 1 presents the range of values for the measures of school staffing in AY2020-2021. It hints at notable differences across districts for all three measures.

*Ranges reflect data for K-12 programs at traditional public schools. Results exclude one 2020-2021 outlier and data on vocational and charter school districts.

^Years of experience in the teaching profession, regardless of place of work.

Source: NJ Department of Education (2022)

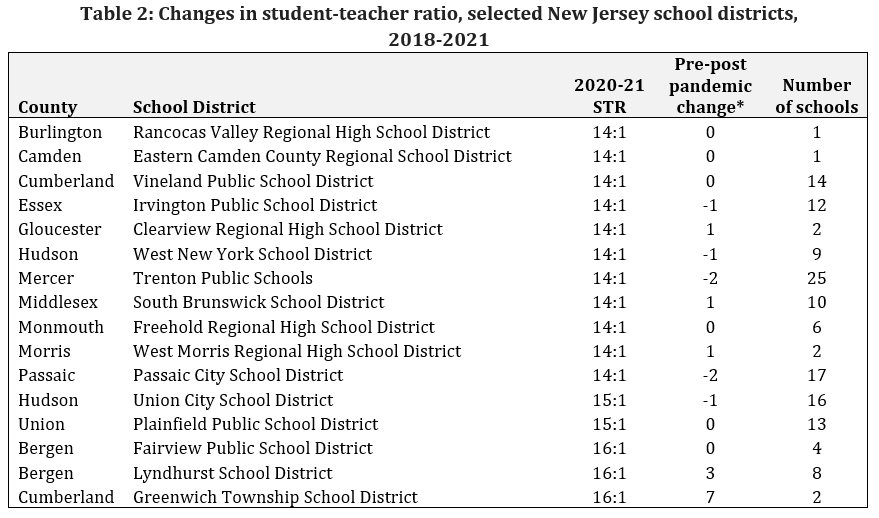

To further examine intrastate variations in measures of school staffing, Tables 2 through 4 present a list of the districts most affected by high student-teacher ratio (STR), low teacher retention rates, and higher rates of less-experienced teachers. Specifically, Table 2 enumerates the school districts in the state that had an STR at or above 14:1 in AY2020-2021, as well as the pre-post pandemic STR change. Table 3 lists the districts that reported one-year retention rates below 80% in AY2020-2021, as well as the change in retention following the pandemic. Lastly, Table 4 shows the districts reporting in AY2020-2021 that their teachers had less than nine years of experience in the profession, as well as the pre-post pandemic change. Since the number of schools in a district may impact staffing changes, Tables 2-4 specify the number of schools per district listed.

*From AY2018-19 to AY2020-21. Change reported in number of students per teacher. For instance, the STR for Greenwich Township School District changed from 9:1 in 2018-19 to 16:1 in 2020-21.

Source: NJ Department of Education (2022)

*From AY2018-19 to AY2020-21.

Source: NJ Department of Education (2022)

*From AY2018-19 to AY2020-21.

Source: NJ Department of Education (2022)

Results in Tables 2-4 suggest that not all school districts with high prevalence of staffing challenges in AY2020-2021 (i.e., as measured by high STR, low retention rates, and less-experienced teachers) experienced noticeable pre-post pandemic changes. Indeed, many districts struggled with staffing issues prior to the pandemic. Examples include: Trenton, which reported a lower STR after the pandemic than before (i.e., 16:1 in AY2018-2019 and 14:1 in AY2020-2021); South Amboy, which had a below-state-average one-year retention rate both before and after the pandemic; and the Orange Board of Education School District, whose teachers had 7.6 years of experience in AY2018-2019 and 7.9 years in AY2020-2021. Some districts, however, experienced notable changes after the pandemic, including: Greenwich Township School District (higher STR), Lyndhurst School District (higher STR), and Edgewater School District (lower retention rates).

A key takeaway from this analysis is that it is crucial to consider district size when assessing the effect of legislation on schools. Since New Jersey has a high share of school districts that are made up of just one or two schools, a thorough analysis of the impact of Bill S3685 needs to include the number of schools (or students) in New Jersey affected by staff shortages, not simply the number of districts (which vary in size).

Maia de la Calle is a postdoctoral associate working with Rutgers Economic Advisory Service (R/ECON™).

References:

Betebenner, D. W., & Wenning, R. J. (2021). Understanding pandemic learning loss and learning recovery: The role of student growth & statewide testing. National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED611296.pdf

Czeisler, M. É., Rohan, E. A., Melillo, S., Matjasko, J. L., DePadilla, L., Patel, C. G., … & Rajaratnam, S. M. (2021). Mental health among parents of children aged< 18 years and unpaid caregivers of adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, December 2020 and February– March 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(24), 879.

Steimle, S., Gassman‐Pines, A., Johnson, A. D., Hines, C. T., & Ryan, R. M. (2021). Understanding patterns of food insecurity and family well‐being amid the COVID‐19 pandemic using daily surveys. Child development, 92(5), e781-e797.

Zamarro, G., Camp, A., Fuchsman, D., & McGee, J. B. (2021). How the pandemic has changed teachers’ commitment to remaining in the classroom. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2021/09/08/how-the-pandemic-has-changed-teachers-commitment-to-remaining-in-the-classroom/

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022, March 3). U.S. schools report increased teacher vacancies due to COVID-19 pandemic, new NCES data show [Press release]. https://nces.ed.gov/whatsnew/press_releases/3_3_2022.asp

Bill S3685 ScaAca (2r), Sess. 2020-2021 (2022). https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2020/S3685

Jennings, R. (2022, October 3). N.J. school district offering $92K salaries to lure retired teachers back to the classroom. NJ.com. https://www.nj.com/education/2022/10/nj-school-district-offering-92k-salaries-to-lure-retired-teachers-back-to-the-classroom.html

NJ Department of Education (2022). NJ school performance report. Performance reports database. https://rc.doe.state.nj.us/download

NJ Department of Education (2022). NJ school performance report. Performance reports database. https://rc.doe.state.nj.us/download

NJ Department of Education (2022). NJ school performance report. Performance reports database. https://rc.doe.state.nj.us/download