By Will Irving

In late July, the outlook for the U.S. economy appeared strong, with some observers suggesting that the Fed had indeed nailed the long-awaited soft-landing even in light of recent cooling in the labor market.[1] Just a week later, however, markets panicked, albeit briefly, as the national jobs report for July showed monthly payroll employment growth slowing to 114,000 jobs, well short of the projected 175,000 job gain.[2] Some invoked the “Sahm rule,” which uses a sharp(ish) increase in the average unemployment rate as a sign that the economy is in the early stages of recession, as the unemployment rate jumped to 4.3%, almost a full point higher than its low of 3.4% in April of 2023.[3]

There were also concerns that the jobs that were being added were limited to only a few sectors (leisure and hospitality, healthcare, local government).[4] Politicians accused the Fed of waiting too long to cut interest rates, driving the economy inexorably toward recession.[5] The markets recovered quickly, however, and attention turned to last Friday’s August jobs report, which was once again awaited with nervous anticipation, as many would view any gain significantly below the consensus expectation of 161,000 jobs as further sign of an impending (or already in progress) recession. The actual gain of 142,000 jobs (along with substantial downward revisions to the gains of the preceding two months) appeared to send a more ambiguous message, spurring a somewhat smaller stock market dip than last month’s report and prompting nuanced debate over minute details of the timing and magnitude of the Fed’s anticipated rate cuts.[6]

And while markets will of course adjust to the reality of where the economy stands, the (over)reaction to the last two employment reports reflects a perhaps unwarranted degree of surprise with respect to the potential magnitude of the slowdown (after all, soft or hard, a landing is still a landing). Indeed, the employment trajectory in New Jersey (and across other states) over the last 18-24 months has to some degree presaged the national trajectory and may serve as a useful guidepost looking forward.

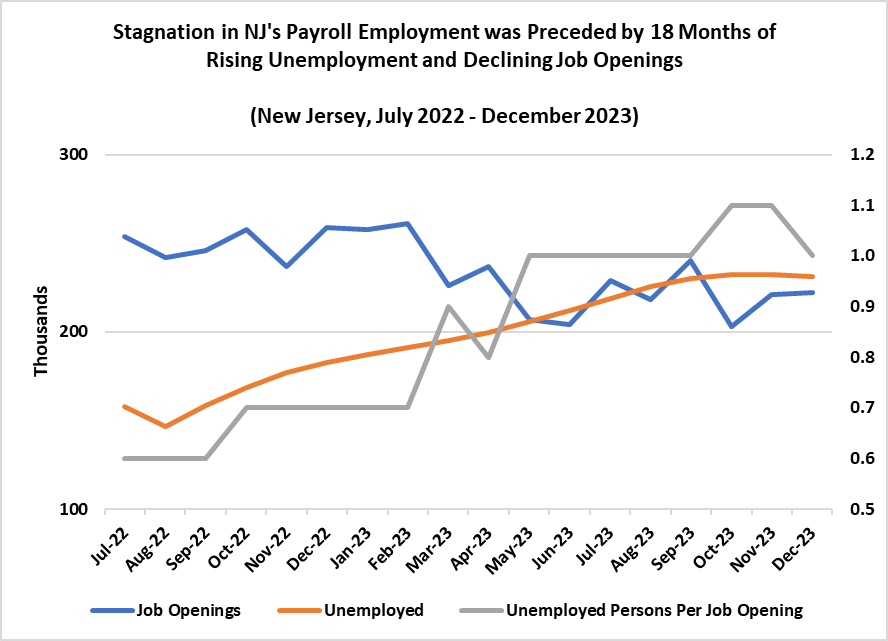

Recall that New Jersey’s unemployment rate spiked from 3.1% to 4.8% over the 13-month period from August 2022 to September of last year and currently stands at 4.7%. During that time, payroll employment continued to grow, though somewhat sluggishly (prior to end-of-year data revisions). However, a R/ECON blog in December noted that the state’s rising unemployment rate and number of unemployed, coupled with declining job openings, indicated that the labor market was struggling to absorb new entrants into positions, likely portending an eventual slowdown in payroll employment growth. Other states had not yet seen a similar spike in the unemployment rate, but it was unlikely that New Jersey would be the only state to see this trend.

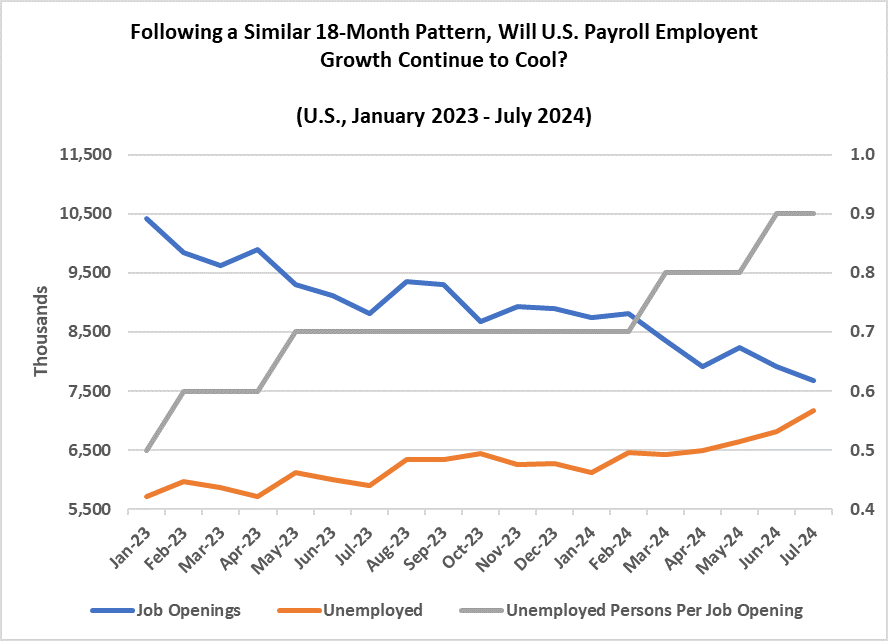

A subsequent R/ECON blog in February noted that unemployment rates across nearly half the states had indeed begun to rise over the second half of 2023, and that New Jersey’s gains in that year, though relatively strong, were largely limited to the healthcare and leisure and hospitality sectors – the same pattern seen nationally now. New Jersey has seen a choppy, largely stagnant payroll employment picture through the first seven months of this year (with private sector employment completely flat). This was preceded by nearly 18 months of increasing unemployment, a decline in the average number of job openings toward pre-pandemic levels, and a resulting climb in the number of unemployed per job opening. Similarly, average job openings nationally have dropped by about 20% since the first quarter of 2023, with the number of unemployed rising and the resulting ratio of job-seekers to openings on the rise.

The point of this observation is not to suggest that nationwide employment or the U.S. economy are soon to screech to a halt. Fed action on interest rates and myriad other factors will act on the trajectory of the economy and labor market in coming months (though debate over the intricacies of the Fed’s rate adjustments may overstate the extent to which such actions can be fine-tuned to assure a desired outcome). Furthermore, New Jersey’s unemployment rate has been stable for half a year. That said, it is worth noting that the behavior of the national labor market is necessarily reflective of state trends, and that some states (e.g., New Jersey) can act as bellwethers as to what lies ahead.

References:

[1] https://www.cnn.com/2024/07/25/economy/us-economy-gdp-second-quarter/index.html

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/02/business/economy/july-jobs-report-what-to-know.html

[3] https://www.nytimes.com/live/2024/08/05/business/stocks-market-crash-economy#the-sahm-rule-points-to-a-recession-heres-what-the-rule-maker-thinks

[4] https://www.cnn.com/2024/08/01/economy/us-jobs-report-preview-july/index.html

[5] https://thehill.com/business/4807717-warren-criticizes-powell-interest-rates/

[6] https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/06/business/stock-market-jobs-report.html