By Jon Carnegie

Over the past several years, a number of policy threads have gained prominence in New Jersey. These include adapting to climate change, advancing social justice, and addressing the needs of overburdened communities. In addition, the pandemic’s disparate impacts on traditionally marginalized populations (low-income, black and brown communities, people with disabilities, and older adults) highlight the need to address mobility and accessibility issues more holistically.

Over the same period, the 15-minute neighborhood concept gained visibility as the global pandemic demonstrated that local access to basic life needs is critically important. Planners and elected officials in cities, including Paris, Barcelona, Melbourne, Ottawa, and Singapore, have embraced the concept as a framework for making decisions about economic development, affordable housing location, and transportation investments, among others. In the United States, for over a decade, Portland, Oregon, has made 20-minute neighborhoods a centerpiece of its comprehensive master plan.

Fifteen-minute neighborhoods provide residents with access to frequent and reliable public transit, parks, schools, gathering places, social services, places to buy healthy fresh food, and other amenities within a comfortable walk or bike ride. Thriving 15-minute neighborhoods rely on not just desired destinations within a 15-minute walk or bike ride but also a safe, convenient, and climate resilient network of walkways, bicycle facilities, and other amenities (e.g., traffic calming, green infrastructure, lighting, and benches) necessary to encourage people to drive less.

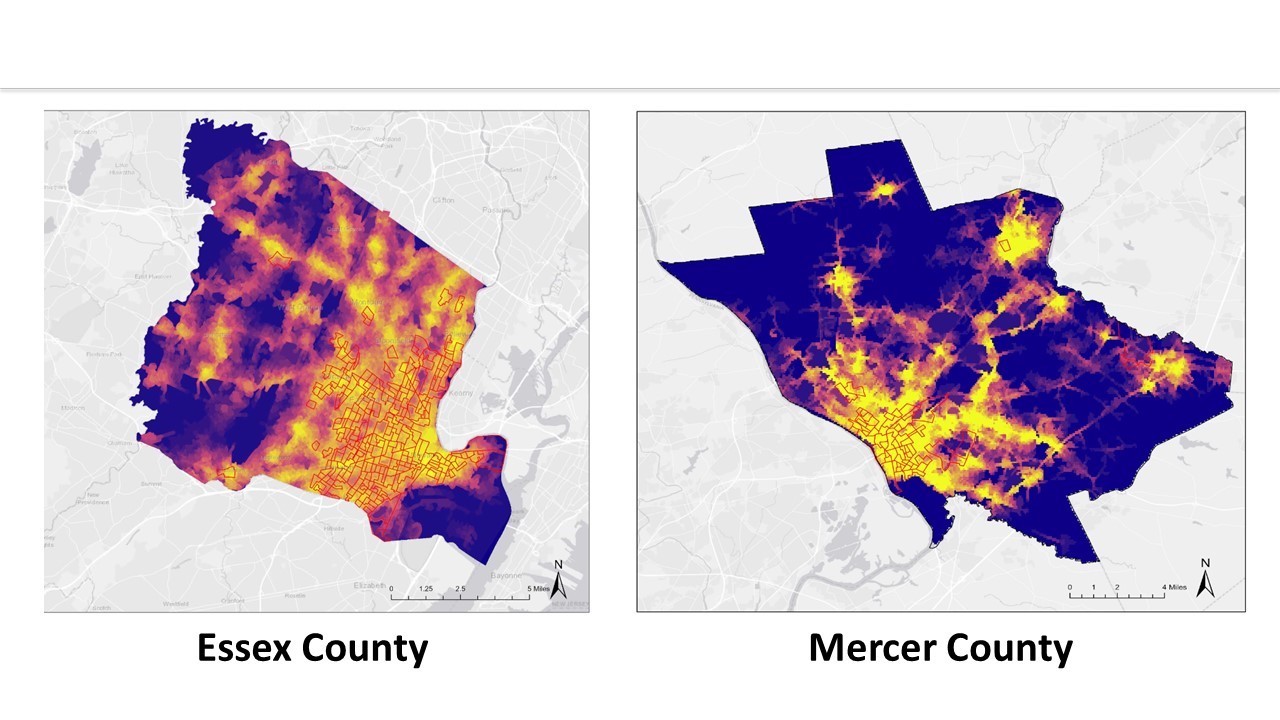

Figure 1. 15-minute Accessibility, Essex and Mercer County, New Jersey

While the idea of 15-minute neighborhoods makes sense intuitively and seems to hold great promise, research shows disparate patterns of 15-minute accessibility across New Jersey. Figure 1 shows “heat maps” depicting levels of accessibility in Essex and Mercer Counties. Older, more-dense neighborhoods, places glowing in hotter shades of yellow and red, have the highest levels of measured accessibility. Suburban and rural places, those neighborhoods and communities showing in cooler hues of blue and purple, exhibit lower levels of accessibility. At the same time, neighborhoods with high 15-minute accessibility often perform poorly in terms of success outcomes such as poverty rates, unemployment, health outcomes, and others. Why is this the case? What needs to change to ensure 15-minute access actually connects New Jersey residents to opportunity and a fair, prosperous future? Can emerging transportation technologies and mobility concepts combine with large-scale investment in complete and green streets to finally dislodge entrenched travel habits? Will local officials and the public support transformational change?

This fall and winter, a team of planners and student researchers from the Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center at Rutgers University will tackle these questions as part of local planning and engagement processes conducted in two New Jersey communities. The planning efforts will explore if and how equitable 15-minute neighborhoods can reshape New Jersey’s landscape while creating a healthier, more just, and resilient mobility system for all New Jersey residents. Insights and outcomes from the local planning efforts will be used to inform statewide policy recommendations related to climate action, equity, social justice, public health, and infrastructure investment. This work is sponsored by the New Jersey State Policy Lab, the Nature Conservancy, and the New Jersey Climate Change Resource Center and supported by the New Jersey Climate Change Alliance, an initiative facilitated by Rutgers University.